In our latest ESRC-sponsored Ask The Expert seminar, Patrick Williams, Senior Lecturer in Criminology at Manchester Metropolitan University, presented his analysis of the Lammy Review of Black and Minority Ethnic representation in the Criminal Justice System, and the durability of racialised disproportionality throughout the Criminal Justice System of England and Wales.

The Lammy Review was set up in January 2016 to find out why official figures show Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups are over-represented in the Criminal Justice System (CJS). David Cameron called for an investigation into this, asking “how we can end this possible discrimination”.

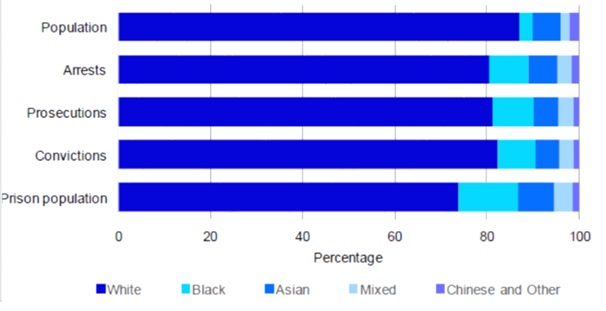

Relative to their size in the population of England and Wales, BAME groups are substantially more likely to be arrested, prosecuted, convicted, and imprisoned, as shown below. Black people are particularly likely to have contact with the Criminal Justice System at all stages; and the prison population is especially disproportionate, comprising almost 30% of individuals from BAME groups.

Ethnicity throughout the Criminal Justice System in England and Wales

Source: MOJ (2015) Statistics on Race in the Criminal Justice System. London: MOJ

What is happening? Why are so many more BAME people – and black people in particular – being arrested? And why is the BAME prison population so disproportionately large?

The role of the police

To answer these questions it is important to understand the processes by which individuals get into the CJS. Here, the role of the police is paramount. Consider, for instance, the treatment of different ethnic groups for drug possession offences. Black people are much more likely to be treated harshly for drug possession than white people: of those found in possession of cocaine, 78% of black people were charged with 22% cautioned; but just 44% of white people were charged, with 56% cautioned.

Differential stop and search rates have been particularly controversial. Black or Asian people are far more likely to be subject to stop and search than white people, including under Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, which allows a police officer to stop and search a person in a designated area without suspicion.

The ways in which police define ‘gangs’ can also have important consequences. Official police databases of gangs in Manchester and London list far more black than white individuals as members of gangs. Given a common assumption that gangs are responsible for a large proportion of Serious Youth Violence (SYV), one might suppose that the perpetrators of these crimes might similarly be disproportionately black. Yet the evidence on this shows the opposite: the perpetrators of 73% of SYV crimes in Manchester, and 94% of SYV crimes in London, are non-black. This is despite a survey showing that almost 80% of young BAME prisoners said ‘the gang’ was invoked in their ‘Joint Enterprise’ court case, compared to less than 40% of young white prisoners.[1]

These findings raise serious questions about how assumptions are made when describing groups and individuals. It also emphasises the importance of providing structural explanations for the disproportionate levels of BAME representation in the CJS, rather than explanations based only on the individual.

The police are not included in the scope of the Lammy Review

It is crucial to understand the role of the police in BAME over-representation in the CJS Yet the police are outside the terms of reference of the Lammy Review, and will not be included as part of the analysis. This is hugely problematic; and means the Review will be condemned to miss some crucial explanations of processes that drive disproportionality and discrimination in the CJS.

Discrimination is ‘hard-wired’ into the Criminal Justice System

There is a variety of ways in which discrimination is ‘hard-wired’ into the CJS. An example is the way in which the Offender Group Reconviction Scores (OGRS) are calculated. The OGRS is a predictor of re-offending based on particular risks – such as age, gender, and criminal history – and is intended to measure a particular individual’s re-offending risk.

These scores are based on a variety of indicators, including a measure of an individual’s first contact with the CJS. However, because of the high levels of stop and search among some BAME groups, this becomes the first point of contact for many young black men in particular. This means that, far from being an individual measure of risk, the OGRS is influenced by structural features of policing.

Another example is given by the way in which resources are allocated to police forces. Resources follow risks – for instance violent crimes are given funding priority. It therefore gives police an incentive to construct an impression of high risk in their area – for instance by providing lists of gang members. Because ‘there is money in gangs’, and because black people are more likely to be listed as belonging to one, policing follows some ethnic groups more than others.

We can respond differently by learning from elsewhere

Yet there are some positives. We can learn better practices by looking elsewhere. An example is the Youth Justice Education Programme, evaluated by the University of Toronto in Canada. The programme aimed to provide support and training to young African Canadians who had been involved in the Canadian criminal justice system. As part of a three-year educational project, participants (or ‘employees’) were paid a salary, and given an academic mentor. Central principles included an acknowledgement that young black people are over-represented in a criminal justice system that treats them differently, and that an ‘ethnic penalty’ exists.

The Youth Justice Education Programme therefore emphasises structural explanations for the over-representation of BAME individuals in criminal justice, and offers an opportunity for the CJS in England and Wales to learn from best practice elsewhere.

[1] https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/publications/dangerous-associations-joint-enterprise-gangs-and-racism

Ask the Expert is the SMF’s lunchtime seminar series, run in partnership with the Economic & Social Research Council (ESRC).

Building on from the success of Chalk + Talk, the SMF Ask the Expert series brings the best policy output from the world of academia into the heart of Westminster.

This new series of events is aligned with current government consultations and parliamentary inquiries, giving policymakers the opportunity to engage with experts in those policy areas.

To suggest a subject for a future Ask The Expert event, please contact the SMF’s events officer Hannah Murphy via hannah@smf.co.uk.