In this blog we look at the possible impact of Brexit on Government targets for the public finances, including deficit reduction and borrowing. We find that the impact leaves many of the spending suggestions made during the referendum campaign unfunded.

Summary points:

- Brexit is likely to slow progress in bringing down Government borrowing. A downturn may also require Government to consider fiscal stimulus to boost the economy.

- Forecasts suggest that the target to eliminate borrowing by 2019-20 will have to be missed.

- The longer-term impact is uncertain, but forecasts point to a negative impact on the finances, reducing Government’s spending power.

- This leaves many spending suggestions made during the referendum campaign unfunded. Government will need to make further reductions to spending to fix the public finances, beyond what was already planned.

The short-term impact

All sides, whether pro-Remain or pro-Leave are now expecting a recession following the UK’s vote to leave the EU.

When growth is weaker, public spending is higher as automatic stabilisers like welfare payments to those on lower incomes kick in. Tax revenues are lower because with lower incomes and profits, households and companies pay less tax.

Back in March, official forecasts were putting growth this year at 2%, with 2.2% next year. Independent forecasters across the board are downgrading their estimates. Some of the early post-vote forecasts put 2016 growth at 1.5%,[1] followed by 0.2% in 2017.[2] These present significant downgrades, with most expecting a “mild recession”, although not on the scale of the fall in GDP experienced after the financial crisis.

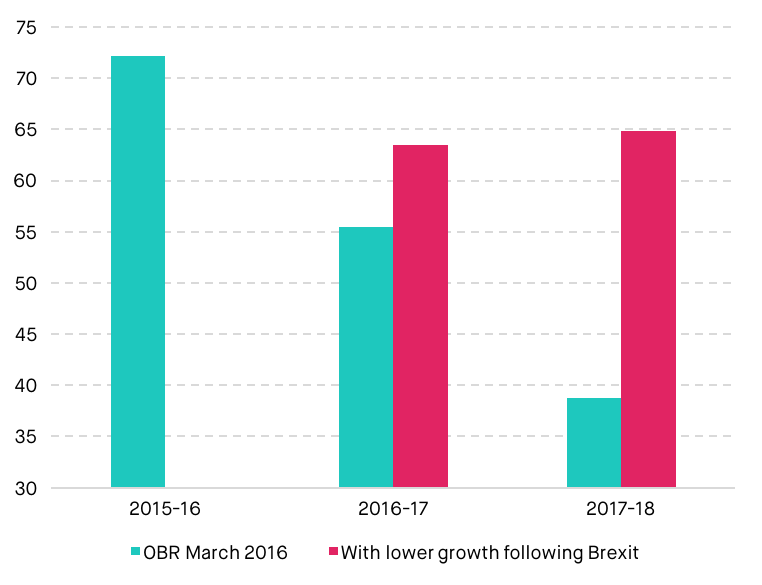

Using ready-reckoners published by the OBR, we estimate that this will mean £8 billion more Government borrowing in 2016-17 and £26 billion more in 2017-18 in cash terms than previously expected, just to cover the gap between higher spending and lower tax revenues. As shown in the chart below, the progress that was expected to be made in bringing down borrowing slows sharply. This is under a very optimistic assumption that the downturn is short-lived, and we return to 2.1% growth in 2018.

Figure 1: Government borrowing – the short-term effects of Brexit (£bn, cash terms)

Notes: Based on ready reckoner of 1% change in GDP resulting in 0.5% of GDP change in borrowing in Year 1, and 0.7% of GDP in Year 2.[3] The Year 2 effects are predominantly due to lagged effects of growth on tax receipts. We assume that growth returns to OBR forecast of 2.1% in 2018, which is most likely a very optimistic assumption. Sources: OBR EFO March 2015; OBR March EFO 2016; IHS forecasts; authors’ own calculations

These figures also assume that the Government continues to implement spending cuts as planned between now and 2017-18. In effect, Government would be running just to stand still.

We have not included the potential benefit that could come from cancelling its net contribution to the EU of £8 billion. It appears optimistic that this would happen within the next two years, given the length of time that it takes for a country to withdraw from the EU under Article 50, and the fact that the Article currently looks unlikely to be invoked immediately. In any case, any saving would not be large enough to fill the budget hole caused by lower growth. And as we show later in this note, there are also a number of spending promises made during the referendum campaign which voters may expect the Government of the day to deliver on.

Further, the value of Government assets, such as stakes in RBS have fallen since the vote. This means that if the Government does go ahead with asset sales, it is likely to receive less than previously forecast, slowing down any progress on reducing the public debt.

Responding to the short-term impact

So far, early post-referendum forecasts of growth are not on the scale of the contraction of the economy experienced in 2008 and 2009. However, a slowdown in growth is likely to push the Bank of England to cut rates to stimulate the economy. With rates at 0.5%, the scope for large cuts are limited.

There would also be a strong case for increasing public spending to support the economy, especially if monetary policy levers are more limited than after the financial crisis.

In the last downturn, investment spending fell by around a quarter from peak to trough,[4] and grew sluggishly for several years after, most likely prolonging the period of poor growth. This is likely to have been in part related to the financial nature of the last downturn, which resulted in bank lending sharply contracting. This time, the nature of any slowdown will be different. However, there are already reports of firms cutting their investment plans.[5]

In response, the last downturn saw the Government of the time increase public sector capital spending, including on housing. In 2008-09, Government increased its capital spending by a third in real terms, and kept it at this high level through to 2009-10. The same Government also temporarily reduced VAT from 17.5% to 15% as part of a fiscal stimulus package.

This time round, temporarily increasing capital spending by a third would cost £23 billion. VAT is now at 20%, but reducing it to 17.5% would cost around £14 billion. These two measures alone would cost around £37 billion. It is not yet clear that a fiscal stimulus package of this size would be warranted, but even if Government only implemented a relatively small package (for example of around £10 billion), borrowing would have to rise year-on–year.

There are also a number of other measures that the Government could consider, such as increasing investment allowances to encourage more private sector investment, cuts to business taxes or acceleration in planned cuts to income tax. Whilst there are no plans for an emergency budget before the Autumn, Government will need to continually monitor indicators of economic growth, so that it can stand ready to intervene if necessary. The next ONS release of GDP figures is on 27 July, however, this will only cover the period up to the end of June. Key potential indicators of the likely economic effects include:

- Markit/CIPS Purchasing Managers’ Index tracking business conditions (data released monthly)

- BCC Quarterly Economic Survey (data released quarterly, next release covering the period after the referendum out in October)

- CBI Industrial Trends Survey (data released monthly)

- Bank of England Agents’ Summary of Business Conditions (monthly updates, next major quarterly release in September)

Regardless of what the Government chooses to do, Brexit firmly stalls progress on deficit reduction.

The medium and longer term

The current Government has a target to eliminate borrowing by 2019-20 and to maintain a surplus in each subsequent year. This fiscal mandate has been approved by Parliament. Any future Chancellor that wished to change the target would need to put a new target before Parliament. Whether the Government remains on course to meet this target depends on how quickly the UK economy recovers from the expected downturn this year and next; and whether Brexit reduces the UK economy’s overall capacity to grow.

In the previous section, our numbers optimistically assumed that we experience a short, mild downturn followed by higher growth in 2018. However, many independent forecasts produced ahead of the vote expected lower levels of GDP to persist to 2019-20 and beyond in the event of Brexit. On this basis, the IFS estimated that in 2019-20, borrowing would stand at somewhere between £28 billion and £17 billion unless further cuts were added to the Government’s austerity plan. This is a large turnaround from an expected surplus of over £10 billion if the UK had voted to remain in the EU.[6]

Under the current mandate, the target is suspended if the OBR assesses that there is a significant negative shock to the UK. This is certainly a possibility given the potential effects of Brexit. This would mean that the Government would not technically be in breach of its own rule. The likely result is that the plan to eliminate borrowing would be postponed.

In the much longer-term, the UK will recover from the immediate economic shock. Long-term growth levels will depend on a number of factors, including the success of negotiating free trade deals independently and the potential for the UK to maintain some access to the EU’s single market. Ahead of the referendum, a range of forecasts were produced by a number of independent bodies. The majority expected Brexit to reduce the size of the economy compared to what it otherwise would be. Based on growth forecasts from NIESR, the IFS expected that Brexit would reduce the amount the Government has to spend by somewhere between £7 billion and £48 billion a year, depending on the terms of trade that the UK is able to secure with the rest of the world.[7] These effects are after taking into account money saved from lower (or no) contributions to the EU.

If these growth forecasts are correct, then in the long-term, Brexit reduces the Government’s spending power.

Spending promises

A number of spending suggestions in the event of Brexit were made during the campaign, on the basis that leaving the EU would mean that the UK would save on the contribution it currently makes.

The UK’s gross contribution to the EU is around £18.8 billion a year, however a substantial rebate reduces this to £14.4 billion a year. Further, much of this is returned to the UK in subsidies for areas such as agriculture, research and regional funding. The amount varies from year to year, but the net contribution averages around £8 billion a year.[8]

The table below shows where 2014 receipts from the EU were allocated. Other analysis shows that there are a number of geographical differences in recipients, with areas such as Wales and Northern Ireland receiving high levels of structural funds and CAP payments.

Table 1: EU-UK funding allocations (2014)

| Area | 2014 receipt (£m) |

| CAP–direct payments | 2,546 |

| CAP–rural development | 555 |

| Regional funding | 1,324 |

| Research and innovation | 642 |

| Erasmus* | 84 |

| Administration | 120 |

| Other | 357 |

| Total | 5,628 |

Source: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmtreasy/122/122.pdf

If there were no changes to economic growth, then in the event of leaving the EU, the Government would experience a net gain of £8 billion a year, and would be free to spend the full £14.4 billion as it sees fit. However, as set out in the analysis above, many of the growth forecasts suggest that Government will overall have less money to spend than if the UK remained part of the EU. This means that spending suggestions made during the campaign are unfunded, and will result in even higher borrowing unless compensated for by spending cuts or tax rises elsewhere.

The various spending suggestions often came from different parts of the campaign, and as such are not entirely consistent with each other. Below we present two scenarios based on spending commitments and suggestions that we are aware of.

Lower bound spending

On its website, the Vote Leave campaign says: “That’s why the safer option is to Vote Leave, stop sending £350 million a week to Brussels, and spend that money on our priorities instead.”[9]

Spending of £350m, or roughly £18 billion a year, is more than the UK’s contribution to the EU budget minus the rebate (around £14 billion), leaving an extra £4 billion to be found from elsewhere, even if Brexit has no effect on economic growth.

Upper bound spending

The campaign also saw a number of more specific spending suggestions. The main ones we are aware of are set out in the table below.

Table 2: Vote Leave ‘spending commitments’ during the campaign

| Spending area | Amount per year (£bn) | Source |

| NHS | £18.2 | Full £350m/week to be spent on NHS – e.g. Gisela Stuart BBC interview

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-eu-referendum-36040060 Note, since the referendum result, many Vote Leave campaigners have said that £350m will now not go to the NHS. |

| Cut VAT on energy bills | £2 | Cut in tax on household energy bills, e.g. Michael Gove & Boris Johnson http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-eu-referendum-36523764 |

| Keep current EU subsidies for farming, poorer regions and research | £5.6 | Vote Leave campaign letter

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-eu-referendum-36527323 |

| Total | £25.8 |

The total of these spending suggestions comes to £25.8 billion.

Given the fact that the public finances are likely to be in a worse state following Brexit, it will be difficult to follow through on any of these commitments. There will be trade-offs to be made between different priorities such as the NHS and protecting current recipients of EU funds. Government will also need to consider spending cuts in a range of other areas. Before the vote, suggestions included removing the triple lock on pensions (potentially saving £6 billion a year)[10], rising in income tax such as raising basic rate income tax by 2p (potentially saving £8 billion)[11] or cuts to public services.

[1] Capital Economics

[2] Capital Economics, HIS, Goldman Sachs http://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/news/article-3658528/Interest-rates-cut-zero-early-2017-Brexit-prompts-economists-slash-UK-growth-forecasts.html ; http://www.cnbc.com/2016/06/26/goldman-sachs-forecasts-uk-recession-in-2017-downgrades-global-growth-forecasts.html

[3] http://budgetresponsibility.org.uk/docs/dlm_uploads/March2015EFO_18-03-webv1.pdf

[4] http://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/uksectoraccounts/articles/economicreview/june2016#gross-fixed-capital-formation

[5] See, for example, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/86d771b6-3bb0-11e6-9f2c-36b487ebd80a.html#axzz4CmV0I4av

[6] http://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/comms/r116.pdf

[7] http://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/comms/r116.pdf

[8] http://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/comms/r116.pdf

[9] http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/briefing_cost

[10] http://www.resolutionfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/DW-slides-for-website.pdf

[11] HMRC Ready Reckoner, rough figures based in 2015-16