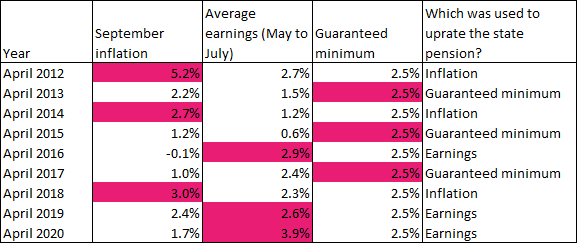

The triple lock, introduced by the Coalition Government, guarantees that the state pension will increase every April by the highest of earnings growth, price inflation or 2.5%. The government uses the September inflation figure (CPI) and average earnings growth between May to July.

In 2018/19 the state pension was paid to 12.7 million people, costing the government £96.7 billion.[1]

How has the triple lock been performing?

Since its introduction the triple lock has increased by the guaranteed minimum of 2.5% three times (2013, 2015 and 2017) and in these years the state pension increase was significantly higher than the increase in wages experienced by those of working age. This means that the state pension has been rising more quickly than earnings and prices.

Analysis conducted by the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) shows that from April 2010 and April 2016 the value of the state pension has been increased by 22.2%, compared to growth in earnings of 7.6% and growth in prices of 12.3% over the same period.[2]

Figure 1: Triple lock growth mechanism 2012-2020 (predicted)

Last week (October 16th) saw the publication of September’s inflation rate. This was the final piece of the puzzle needed to confirm the increase to the state pension in April 2020.

ONS figures show that inflation was 1.7% in the 12 months to September, whereas earnings growth in May to July was 3.9%. As earnings growth was larger than the guaranteed minimum of 2.5%, in April the state pension is expected to increase by 3.9%. This means the Basic State Pension will increase by £5.05 to £134.25 per week (to the nearest 5p) – this is an annual increase of £262.60. The New State Pension will increase by £6.60 to £175.20 per week – equivalent to a rise of £343.20 per year.

Time for change

An uprating of the state pension by 3.9% will lead to a large increase in the cost to the government. The number of people above state pension age is expected to slightly fall in the coming years due to changes in the pension age, yet the cost of the state pension will continue to rise. The OBR estimated that in 2020/21 the state pension would cost the government £101.5bn and this was based on earnings growth of 3.1%.[3]

Research conducted by the Social Metrics Commission shows that over the last 15 years pensioner poverty has reduced drastically, falling by 10% between 2000/01 and 2014/15. During this time frame working-age adults saw zero change in their poverty rates.[4] This suggests that government policy focused on reducing pensioner poverty is doing so at the expense of those of working age.

There has been some political support for the removal of the triple lock, in their 2017 manifesto the Conservative Party stated they would replace the triple lock with a “double lock” from 2020 (a removal of the 2.5% minimum guarantee)– however this plan was later dropped during negotiations with the DUP. The Cridland Review of the State Pension Age (SPA) also recommended the removal of the 2.5%.[5]

The 2.5% minimum increase guarantee is likely to become redundant over the next couple of years if earnings growth forecasts are to become a reality. Over the long term the triple lock starts to become unaffordable. If the triple lock continues the cost of the state pension will increase from 5.0 per cent of GDP in 2022-23 to 6.9 per cent in 2067-68.[6] Without large changes to the state pension age the continuation of the triple lock is likely to increase welfare spending and lead to difficult decisions to be made on the government’s spending priorities.

Figure 2: State pension spending projections

Introducing a double lock, where the state pension would rise by the highest of earnings growth or inflation (removal of 2.5% guarantee) reduces the cost of the state pension compared to the triple lock by 0.2% of GDP in 2067/68. A single lock (earnings growth link) means that spending on the state pension would be 1% of GDP lower in 2067/68.[7]

Only legislated changes to the SPA are represented by the blue line in Figure 2. Here the SPA rises to 68 in 2046, the current legislation, and stays there for the remainder of the forecast period. In this scenario the cost of the state pension is 0.6% of GDP higher in 2067-68 relative to the baseline projection. This highlights the importance of further increases to the state pension age regardless of how the value of the state pension is uprated.

Making changes to pensioner benefits is a difficult area politically for the government – particularly when changes will make very little difference in the immediate future. However, it is clear to see that in its current form the triple lock is unsustainable. This raises the question of where should the policy go next? Politicians should go further than simply replacing the triple lock with a double lock, which is still an expensive policy, and look at linking the state pension to earnings. In this scenario the relative position of pensioners in society is not altered.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/benefit-expenditure-and-caseload-tables-information-and-guidance/benefit-expenditure-and-caseload-tables-information-and-guidance

[2] https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/8942

[3] OBR, Economic and Fiscal Outlook (2019)

[4] SMC, Measuring poverty 2019 (2019)

[5] Cridland review (2017)

[6] OBR, Fiscal sustainability report (2018)

[7] OBR, Fiscal sustainability report (2018)