This analysis sets out how reforms to alcohol duty could boost pub sales by 100 million pints a year, providing a lifeline to the hospitality industry and reducing harmful drinking.

Britain’s ability to take a different regulatory approach to the European Union across a range of areas has been hard-won. It is likely to come with a significant price tag, in terms of the economic costs of Brexit. That makes it all the more important that the Government makes wise use of its newfound powers and scope for action. In 2019, the SMF called for a fundamental overhaul of the way the UK taxes alcohol, which was in significant ways constrained by EU Directives. Last year, the Government did indeed launch a review of the alcohol duty system, seeking ways to make it more rational. With the pandemic having hit hospitality hard and some evidence of a rise in high risk drinking under lockdown, the case has only got stronger for a fundamental restructuring of the duty system to support both public health and the licensed trade.

The SMF has contributed to the ongoing consultation, advocating the changes we set out in our 2019 Pour Decisions report: a system that taxes products of equal strength at the same rate and stronger products at a higher rate, eliminating the perverse incentives that support cheap, high strength products like ‘white cider’. Fundamentally, we believe that the level of tax should reflect the level of harm it is liable to cause – and stronger drinks, containing more alcohol, are associated with greater harm.

In this blogpost, we want to focus on our other major recommendation: that alcoholic drinks sold in the off-trade (supermarkets and off-licences) should face a higher level of alcohol duty than drinks sold in the on-trade (pubs, bars and restaurants). Again, this is because we believe that off-trade alcohol is associated with more harm. Not because drinking at home is intrinsically more problematic than drinking in a hospitality setting. That case can be argued both ways. On the one hand, drinkers in the on-trade are supervised by what we hope are responsible servers. On the other hand, drinking outside the home involves travelling further and interacting with more people, increasing the chances of drink-driving or violence.

The key difference between the on-trade and the off-trade is that off-trade alcohol is much cheaper: a pint of beer in a pub costs about three times the equivalent amount bought from a supermarket. And as a general rule, cheaper products are more likely to be consumed by heavier drinkers. Harmful drinkers account for 32% of alcohol-related revenue in the off-trade, compared with 17% of revenue in the on-trade. So if we want to target alcohol taxes at drinkers who are consuming at riskier levels, we should tax off-trade alcohol more.

There are different ways that the alcohol duty system could be redesigned to ensure taxes fall more heavily on the off-trade. For example, Australia levies higher taxes on packaged beer than on draught beer – but this does not affect the cost of other drinks. The Republic of Ireland has considered a ‘lid levy’, with an additional charge for closed containers – but since the levy is proportionate to the price of the drink, it would be lower on cheaper products, precisely the opposite of what we are seeking to achieve.

What SMF has proposed instead is a ‘pub relief’ that allows pubs, bars and other licensed premises to claim back a percentage of the duty costs that they face. This would have the benefit of ensuring that the duty rebate is passed directly to pubs: publicans have in the past complained that they have not seen any benefit from cuts to alcohol duty because the duty is paid by brewers who may not adjust their prices down accordingly.

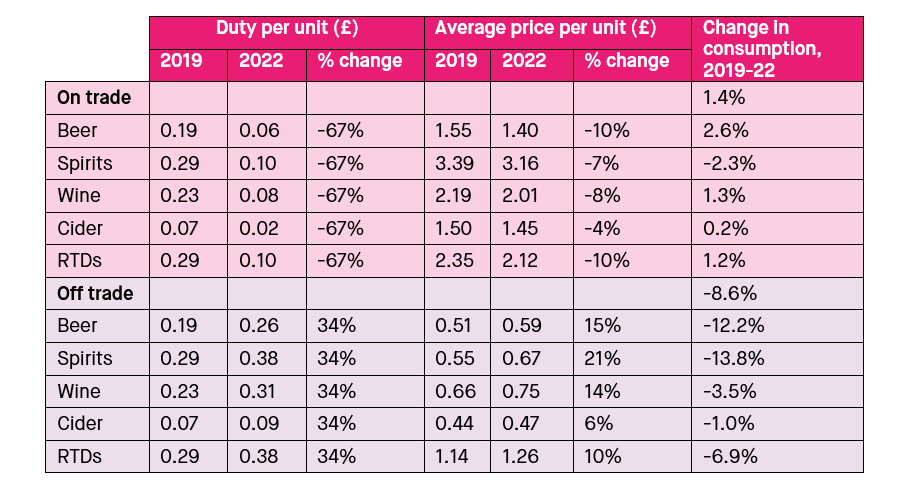

To examine the impact of such a scheme, we have modelled the effect of a 75% duty discount for the on-trade. For such a scheme to be revenue neutral (in keeping with the terms of the duty review), off-trade alcohol duty would have to rise by 34%. Translated into prices, that would imply that the cost of a pint of beer in the pub would fall by 36p (or 10%), whereas the cost of a can of beer from the supermarket would rise by 14p (or 15%).

Such a change could reduce harmful drinking: overall alcohol consumption would be expected to fall by 5.7% relative to 2019 levels (our model abstracts away from the unpredictable impact of the pandemic). That is a comparable reduction to the estimated effect of minimum unit pricing in Scotland.

Modelled impact of a 34% increase in alcohol duties and a 75% pub relief

The move could also offer some assistance to the hospitality trade by reducing the price differential between the pub and the supermarket. A 2.6% increase in on-trade beer sales amounts to around 95 million additional pints sold a year. Overall on-trade sales would be expected to be 1.4% higher than in 2019. That may not sound like a lot, but it has been over 20 years since aggregate on-trade sales have gone up, despite a series of real-terms cuts to alcohol duty. In cash terms, it would represent over £350 million more in sales.

The Government may be reluctant to see prices in the off-trade rise by as much as our modelled scenario implies, or at least not too quickly. A smaller pub relief would have proportionately smaller benefits. For example, if the pub relief were set at 25% and off-trade duty increased by 9%, total alcohol consumption would only fall by 1.4%.

Among the many big decisions the Chancellor must make in the coming weeks is the future of alcohol duty. In the face of a hospitality industry facing unprecedented challenges, he should resist the temptation to continue with nominal freezes that have cost the exchequer billions and undermined public health. The bold course of action would be to rebalance alcohol duty with a higher rate for shop-bought alcohol, offset by a discount for the on-trade. That could nudge people back into pubs, reducing harmful drinking and maybe even shift the country towards a better drinking culture. We’ll drink to that.