Increasing police numbers can reduce crime rates, and yet - as Richard Hyde points out - it is an aspect of policing that isn’t as prominent as it should be. As crime will likely become more complex, Hyde calls on police and policymakers to invest in increasing police numbers, so that we can not only to stay on top of the current high levels of crime, but also reduce them substantially.

On the 8th of March, Sir Michael Barber’s impressive Strategic Review of Policing in England and Wales (“the review” or “Barber review”) was published. It sets out a vision for policing that all policymakers need to consider seriously. It provided a detailed overview of many of the failings of the police service and the growing criminal challenges the police service in England and Wales is failing to rise to sufficiently. It made a slew of recommendations, many of which – if implemented – would significantly improve the increasingly deficient policing status quo.

However, the report does not engage in any great detail on the issue of police officer numbers. This is a notable gap in the conclusions, despite it acknowledging the role that cuts in police manpower have played in recent years in the police’s declining performance in many areas.

Police staffing is particularly important because England and Wales are comparatively under-policed societies, given that:

- Police numbers are now well-established as an important factor in determining the volume of crime perpetrated.

- It is more labour intensive to tackle the complex crimes that are increasingly coming to dominate the crime-types being committed against the people and households of England and Wales.

An absence of confidence in the police among much of the population

The Barber review highlights levels of confidence in the police service that should concern officers, at all levels of the service, and policymakers. It notes that:

“…the percentage of people who think that the police do a good or excellent job has been falling steadily in recent years”.

The model of policing in England and Wales is one of “policing by consent”. When public confidence in the police is declining, the “consent” on which its legitimacy and effectiveness relies is at risk. Further, persistently low levels of confidence could “break the model” entirely.

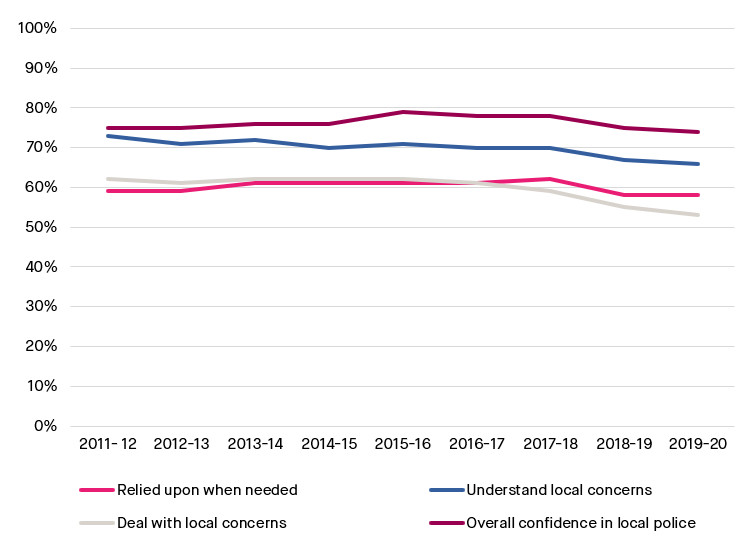

Figure 1 shows the trend in aggregate levels of confidence among the public of England and Wales in their local constabulary and the police service more generally over this decade:

- Across the period, the proportion of the public reporting they had “confidence in the police” was stable, at around three-quarters.

- The portion saying that their local police can be relied upon when needed has been similarly stable between 2011-12 (59%) and 2019-20 (58%).

- The proportion of the public agreeing that their local police “understood local concerns” declined markedly from 75% in 2011-12 to 66% in 2019-20.

The percentage of the public saying that their local police “deal with local concerns” also declined noticeably. In 2011-12, 62% agreed with this statement, but in 2019-20 this had fallen to 53% of the public.

Figure 1: public attitudes towards their local constabulary and the police service in general, April 2011 – March 2020

Source: CSEW

Figure 1 suggests a substantial proportion of the population across England and Wales has little confidence in their local constabularies:

- Less than six in ten people believe their local police can be “relied upon when needed”, implying that more than four in ten do not consider their local police reliable.

- The trend in two of the key measures of confidence (“understanding local concerns” and “dealing with local concerns”) is downward.

- Just over half of people believe their local constabulary “deal with local concerns” indicating that nearly half do not believe they are dealing with local problems.

The situation in London in particular is worse. As Barber indicated in this recent report:

“In London even fewer people say they trust the police and think that the police will treat them fairly. These signs of a deterioration in public confidence are, no doubt, linked in part to recent high-profile cases of police misconduct”.

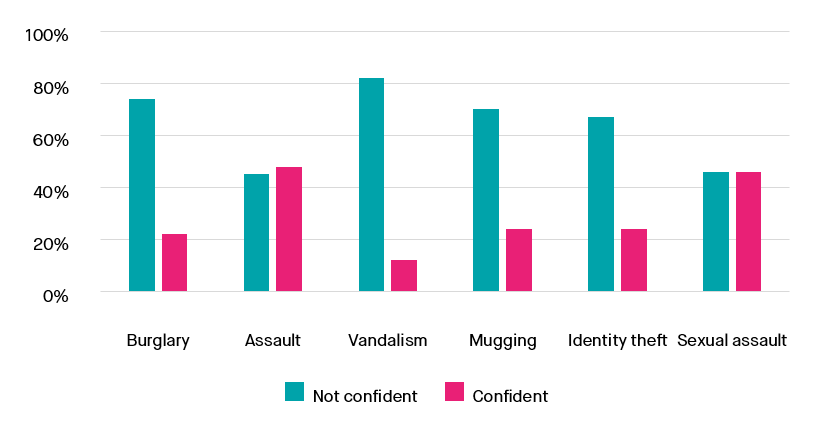

Other data also indicate that large swathes of the public do not have confidence in the efficacy of the police. Figure 2, for example, shows that across a range of criminal activities, majorities of the public would not be confident the police would be able to find and arrest the perpetrator(s).

Figure 2: confidence that the police will find and arrest the perpetrator of selected criminal activities, 2020

Source: YouGov

Figure 2 highlights that only 22% of the public agreed they were “confident” that the police would find and arrest the perpetrator(s) of a burglary, while 74% were “not confident”. Of the crime categories listed in Figure 2, only assault and sexual assault showed an even split between those “confident” and those “not confident” that the police would apprehend those who committed such crimes. Further, the data presented in Figure 5 suggest that the public’s confidence in police efficacy is greater than what the “detected” crimes data warrants. Therefore, it seems likely that confidence levels could fall further if the true picture percolates through to public..

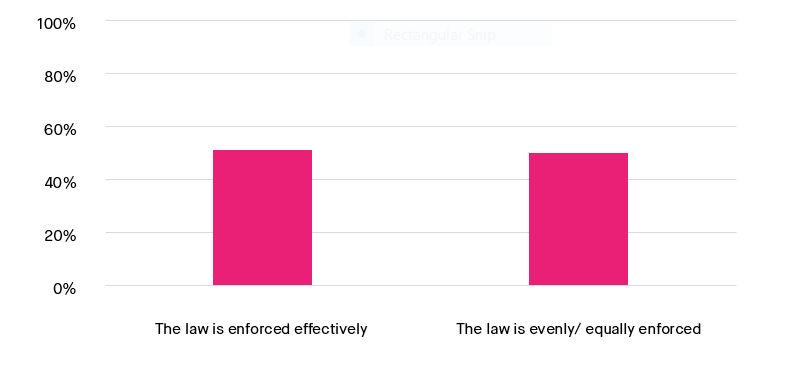

The lack of confidence in the police’s performance is further reflected in large proportions of the population not feeling confident in the enforcement of the law more generally. Figure 3 for example, shows that a small majority (51%) of the public believe that the law is “effectively enforced” and precisely half (50%) consider the law is “enforced equally”.

Figure 3: effective and equal enforcement of the law, 2021

Source: Opinium

Policing by consent relies on the population buying into the effective and equal enforcement of the law. Given this, the public opinion data outlined in Figures 1, 2 and 3 portray a troubling picture. Taken together, they suggest that the police (and policymakers) have some significant challenges to overcome if the police are to be seen as effective by the kind of majority of people needed for the “policing by consent” model to persist.

Why public confidence is not high

The data presented in figures 4 and 5, which highlight the two most important police performance benchmarks, key performance metrics help explain why public confidence in the police isn’t as high as an effective consent-based police service would reasonably expect it to be, if the model is to be sustained.

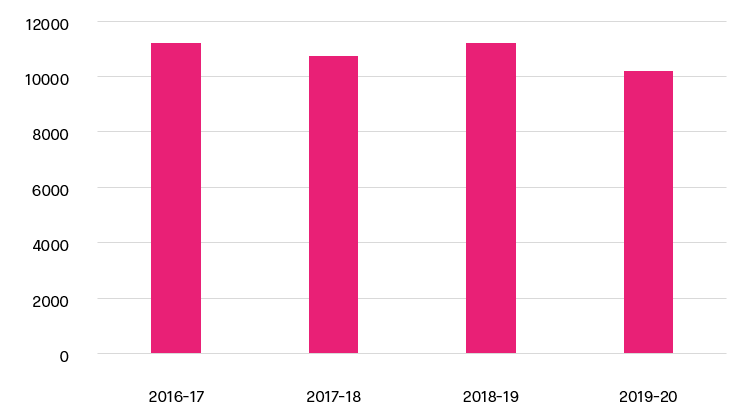

Figure 4 highlights Crime Survey of England and Wales (CSEW) findings, which show that there have been – consistently – more than 10 million crimes committed against people in England and Wales between 2016-17 and 2019-20, with around one-in-five of the public likely to be a victim of at least one crime, in any given year.

Figure 4: crimes reported by the public to the Crime Survey of England and Wales (in 000’s) between April 2016 – March 2017 and April 2019 – March 2020

Source: Crime Survey of England and Wales

The second key benchmark that reflects poorly on police performance is the “detection” or “clear-up” rate. The Barber review stated that:

“Detecting crime and bringing offenders to justice are core police functions. The available data shows a substantial deterioration in police performance at bringing offenders to justice…”.

Barber added that:

“…the police response to many crimes such as burglary had become perfunctory; too often a crime number is issued for insurance purposes but there is no investigation”.

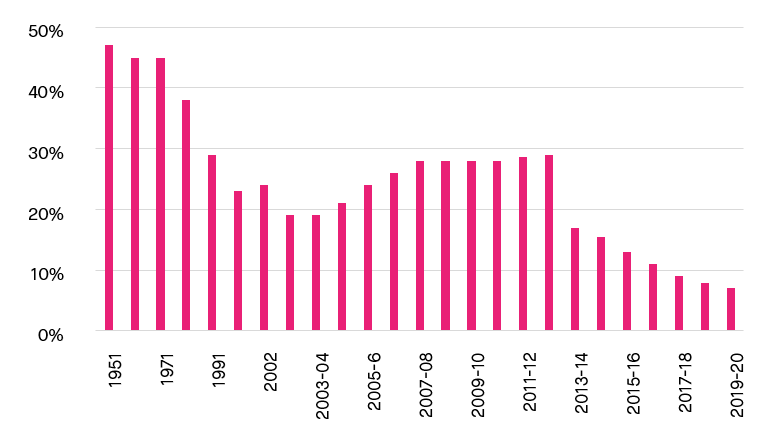

As Figure 5 demonstrates, nearly one in two reported crimes were “detected” in 1951. By the year 2019-20 the proportion of reported crimes that ended in a “charge or summons” was 7%.

Figure 5: proportion of Police recorded offences “detected”, in selected years

Source: Home Office. Note: ”detection” captures a number of outcomes. Further, the way of counting “detections” has changed over time. Examples of those changes include: the addition of offences, changes to the criteria around “non-sanction detections” and the introduction of the National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS) in 2002, among others. More recently the use of “detection” as a measure of police effectiveness was replaced in 2013-14 with a new system focussed on “outcomes”. Data presented in Figure from 2013-14 onward reflect this and detail the proportion of recorded crime that led to a ‘charge or a summons”.

Box 1 illustrates the police’s lack of efficacy against some of the more complex crimes that have become prominent in recent years, by focusing on the example of fraud.

Sources: Barber (2022); Gee, J and Button, M. (2021); HMICFRS (2019) and SMF (2022)

One in six people highly prioritise crime

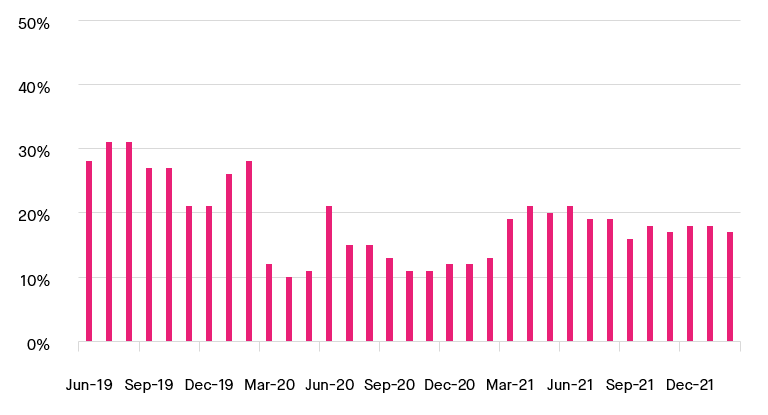

Given the high crime levels and poor “clear-up” rates, it is unsurprising that crime is a prominent issue among the public, with one in six placing it in their top three “most important issues facing the country” at the moment, as highlighted in Figure 6.

Figure 6: proportion of the British population citing crime as one of the top three “most important issues facing the country”

Source: YouGov. Note: the base for this YouGov polling is Great Britain, not England and Wales.

Figure 6 highlights the ups and downs of crime as a prominent issue facing the country since mid-2019. Currently crime is cited by 17% of the public as one of the three “most important issues facing the country”.

The elephant in the room

A link between police numbers and police performance

The Barber review does not go into a great deal of detail about the issue of overall police numbers in England and Wales and their potential positive impact on crime levels. However, it does acknowledge the harm that resulted from the cuts in funding and the consequent reduction in the number of officers during the 2010s:

“…over those years, police officer numbers fell from an all-time high of 143,000 to 123,000”

Barber adds:

“…there are many reasons why some key measures of police performance have deteriorated in recent years. We particularly need to highlight one: austerity. Between 2010 and 2014 total funding for the police fell by approximately 14 per cent, and by a further 2 per cent by 2018…we are undoubtedly still living with the consequences of a decade of significant cuts to police budgets…”.

The current strength of the police force

England and Wales is currently in the midst of an effort to increase the number of police officers by 20,000 above the 123,189 officers that were in place in March 2019. By March 2021 the numbers had grown by 10%, with their strength at just over 135,000, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: policing numbers, March 2021

| Category of police staff | |

| Full-time Equivalent (FTE) police workers across the 43 territorial forces |

220,519 |

| FTE police officers across the 43 territorial forces |

135,301 |

| National Crime Agency officers (warranted and non-warranted) |

5,077 |

Source: Home Office

England and Wales is (comparatively) under-policed

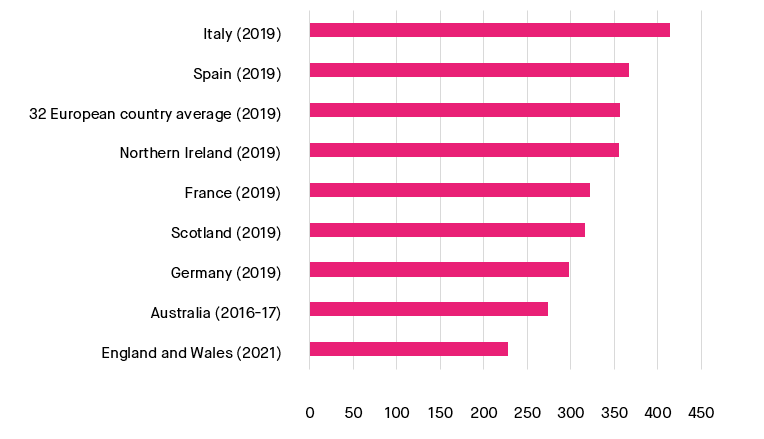

If the 20,000 increase in police officers is achieved by March 2023, England and Wales will remain comparatively under-policed. This is clear when officers are measured on the basis of the number of police per 100,000 of the population. The data presented in Figure 7 shows the sizeable deficit in officers between England and Wales and some comparable countries, when analysed in such a way.

Figure 7: police numbers per 100,000 of the population in selected countries, various years

Sources: House of Commons Library, Eurostat, Australian Productivity Commission

The comparative deficit in police officers in England and Wales is important for two reasons:

- There is a clear link between officer numbers and crime levels.

- The changing nature of much of the crime being committed – which is more labour intensive to tackle – implies a need for more police staff to keep on top of crime levels, let alone play a role in driving them down.

A direct association between police numbers and crime levels

There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating a clear link between police numbers and crime levels. Research commissioned by HMICFRS noted that:

“…the studies that have appeared over the last 15 years…[1996 to 2011]…do indeed suggest that there is a significant negative association between the numbers of police (and/or the number of arrests made) and the level of…crime…The research has varied considerably in terms of methodologies, time-spans, and countries, but has still generated broadly similar findings…there is a real effect of police numbers on…crime”.

While, a more up-to-date analysis highlighted that more police:

“….has a substantial…effect on serious crime. There is also consistency with respect to the size of the effect…Most estimates reveal that a 10% increase in police…yields a reduction in total crime…of 3%…[and]…studies that consider violent crime tend to find reductions ranging from 5 to 10%”.

The body of criminological evidence is clear; an increase in officer numbers (utilised competently) is likely to lead to reductions in overall levels of crime and in-turn social and economic savings to the locally affected areas and the country as a whole.

The complexity of more and more crime makes policing more labour intensive

Sufficient staffing is particularly pertinent, in a time when the nature of much of the crime committed is becoming more complex , as HMICFRS has highlighted:

“The number of crimes recorded by police has risen, the complexity of many crimes is increasing, and there are fewer officers and staff to investigate”.

The “new complexity” of crime – as one criminologist noted – is driven in large part by factors such as technology and the sophisticated organised criminal gangs behind much of it. Specifically, the last thirty years has seen the emergence of:

“…new forms of harm…Identity theft, people trafficking and exploitation, investment scams and internet fraud and other emerging crimes…[which]…present new challenges for the police, who are now required to…deal with criminal networks and changing modus operandi…”.

Increasing officer numbers up to the European average

If constabularies across England and Wales were able to increase overall officer numbers to the 2019 European average of 357 per 100,000 of the population (from the 228 per 100,000 that it was at the end of March 2021) England and Wales would have around 213,200 officers in place across both countries. Achieving this would require recruiting approximately 70,000 more police, over and above the 20,000 already pledged, as well as ensuring existing officers are replaced when they leave the service.

Such an increase would require an extra £8bn of expenditure by central government and Police and Crime Commissioners – the exact mix of national and local spending would need to be determined as part of any police expansion plan and efforts to re-organise the structures of policing. The extra expenditure would require total spending (central and local) on the police service to rise to just over £23bn a year, from the £15bn that was spent in 2020-21.

If government and the police are serious about reducing crime levels from the current, more than 10 million incidents a year, a substantial proportion of the additional officers (complemented by expert civilian support staff and prosecutors where necessary) would need to be recruited on the basis that they will become specialists in tackling some of the more complex crimes that now dominate the crime figures, such as fraud (along with closely associated criminal activities like cyber and organised crime).

Maximising the full benefits of an expanded police service would require a shake-up of the organisation, leadership, management, training and funding of the police in England and Wales. The debate as to what such changes might involve is beginning to get underway. A set of proposals for improving the efficacy of the fight against economic crime in general and fraud in particular have recently been set out by the Social Market Foundation. Other, wide-ranging potential changes to how policing is best organised were recently proposed by Sir Michael Barber is his Strategic Review of Policing.

A reduction in crime and the cost of crime

If the extra 70,000 officers had been in place in the year 2019-20, it is likely there would have been at least 1.4 million fewer crimes perpetrated against households and residents in England and Wales. Further, this could have resulted in gross savings to society of approximately £11.1bn and a net saving of £3.5bn (over and above the extra £8bn of additional expenditure on policing required to increase numbers to 357 per 100,000 residents).[1]

[1] Calculated using the Home Office’s aggregate (£50.1 billion at 2015-16 prices) estimate of the social and economic cost of crime to individuals, across England and Wales. Source: The economic and social costs of crime (publishing.service.gov.uk)