‘A change is gonna come’

Next month, the George Osborne policy of freezing benefits will come to an end. The freeze began in 2016 but was announced in 2014, in the context of the Cameron Government fiscal retrenchment. The freeze aimed to save money from the welfare budget[i], which is the largest single item of government expenditure: welfare accounts for over a third of all government spending. The freeze, which pared more than £16 billion from welfare spending, is arguably the most significant welfare policy decision of recent years, though it receives relatively little public attention.

Far more prominent is another policy that began in the Coalition era, Universal Credit (UC). It aims to:

- Simplify the complex benefits system in the UK by rolling six means-tested benefits and tax credits into a single monthly payment.

- Improve work incentives by reducing the financial penalties for working e.g. lowering the benefit withdrawal rates.

Since it was first promised, UC has been plagued with delivery and implementation problems. In the context of “austerity” policies, it has it has become more controversial over time.

Despite their scale and impact, UC and the benefits freeze were not fundamental reforms to UK’s ‘liberal’ welfare system. They were changes within the existing paradigm.[ii] Universal Credit is consistent with the underlying characteristics of a ‘liberal welfare’ model, as Gosta Esping-Anderson characterised the UK’s welfare state in his seminal analysis The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. For example, UC is a means-tested safety-net measure, it focusses on getting people back into any work and then supporting people in work at low-wages where necessary. It works ‘with the grain’ of a flexible labour market facilitating the supply of labour for business. In Esping-Anderson’s analysis, policies like UC are based on the ‘liberal’ view that labour is primarily a factor of production. Welfare measures which reflect this are seen by Esping-Anderson as having a limited ‘de-commodifying’ effect. This is in contrast to welfare models in other countries in other parts of the world, which embody different assumptions including seeing labour primarily as a vocation and not as a commodity. Consequently, the welfare measures in such countries ‘de-commodify’ labour more extensively than under a ‘liberal’ welfare model like the UK, through stronger protections and less of a focus on facilitating a flexible labour market for capital.

However, the end of the ‘benefits freeze’ and Universal Credit are harbingers of three significant challenges for the welfare state over the next decade:

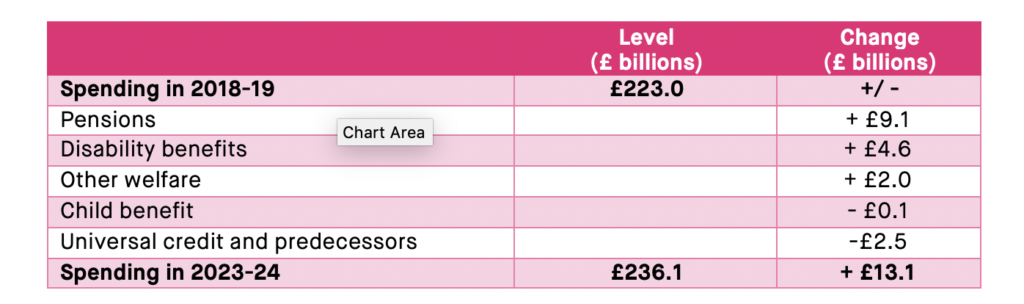

- A return to growing welfare expenditure for the foreseeable future (see table 1);[iii]

- The efficacy of central government leadership on welfare issues;[iv]

- A reignited debate about the desirability of welfare based more heavily on means-testing.[v]

Table 1: Sources of change in real-terms welfare spending: 2018-19 to 2023-24

Source: OBR

Beyond the end of the benefits freeze and the controversy of Universal Credit implementation, there are two further factors that will have profound impacts on the UK’s welfare state and its sustainability in the long-term, in its current form. These factors which are yet to be fully reflected in current political, media and public debate about welfare, which tends to focus on more immediate and short-term issues.

Demographic change

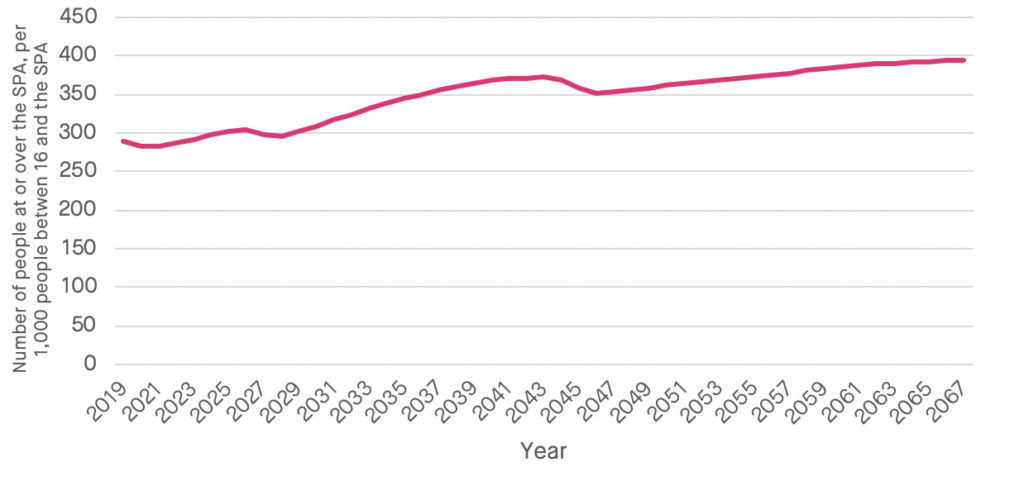

The first factor is demographic change and our ageing society. By 2066, there are expected to be around 5.1 million people aged over 85, making up 7 per cent of the population. Large shifts in the demographic balance will result in an increase in the Old Age Dependency Ratio (OADR), i.e. the number of people at the State Pensions Age (SPA) or older compared to the number of people between 16 and the SPA.[vi] Figure 1 highlights the projected increase in the OADR in the UK for, approximately, the next half a century.

Figure 1: forecast increase in the OADR

Source: ONS

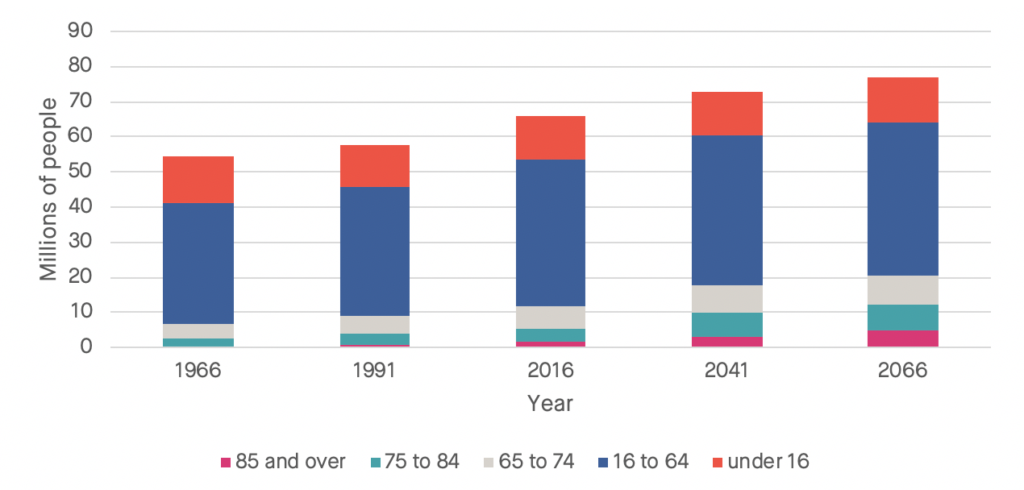

Figure 2 shows the ageing trend in UK society by showing actual and projected changes in selected years in the demographic mix of the UK population. Highlighting, using a different metric, a similar future trend to that shown in Figure 1 through the OADR.

Figure 2: Population by age group, in selected years

Source: ONS

The implications of these demographic trends are likely to be significant. The most obvious impact is that welfare expenditure will continue to rise. That expenditure – as the OADR in Figure 1 illustrates – will be supported by relatively fewer and fewer workers over time. A less widely spread burden has consequences for inter-generational fairness and potential impacts on the length of working lives and the weight of future tax burdens on those who are in work and businesses, which in-turn could have a bearing on future growth rates.

Economic transformation

The second factor is the wide-ranging structural transformation of the economy driven by the fourth industrial revolution (4IR). The 4IR will have far-reaching implications for the functioning of the labour market and working patterns.[vii] [viii] While currently no-one knows for certain what will happen in the long-run as a result of the 4IR,[ix] and many argue that the overall net impact will be positive,[x] a number of disruptive impacts on the labour market and work are widely expected, which pose challenges for welfare states. These include:

- Further growth in the ‘gig economy’ and self-employment more generally, which could impact taxes and contribution levels.

- For some, greater income volatility, more precarious work and perhaps lower overall earnings than would have been the case compared to more traditional full-time employment.

- Increase technological unemployment. This may be temporary as people shift from shrinking industries to expanding ones driven by new technology. For some people however, the unemployment will be more persistent and moving to another industry will be more challenging. There are numerous examples of the decline of industries creating long-running unemployment problems. It seems certain that whether temporary or more persistent, it will become a more frequent and widespread feature of economic life, as factors such as automation spread through the economy.

- More instances of under-employment – for at least a portion of some people’s working lives. This might be a result of reductions in the working week (as labour becomes more and more substitutable by capital) and overall incomes fall, and some categories of workers are unable to sustain their living standards.

The pressure on the welfare state under such volatile circumstances will not only be financial but functional. Sustainability will not just be a question of resources, but also whether its design is suitable to deliver what people need in an era of a fundamentally transformed economy, with the prospect of regular technological disruption (and the economic consequences of such ‘churn’ like those described above) becoming more frequent. As no one knows for sure what the consequences of the 4IR will be, the future welfare state will have to have the flexibility to respond to the unexpected.

There are nascent yet growing debates about policy responses to the potential disruption of automation and other technologies which are driving the 4IR, including considerable momentum behind the idea of a Universal Basic Income (UBI). Others engaging in the nascent debate about how national welfare regimes should respond to the 4IR are proposing alternatives such as a Universal Jobs Guarantee (UJG) and Universal Basic Services (UBS).

Given the emerging trends and growing debate over potential ways of adapting the welfare state to the new, emerging, technological and economic dispensation, 2020 would seem the ideal time to re-examine the UK’s welfare state. In particular, to re-examine its underlying principles and assumptions, and in turn the institutional structures that deliver welfare.

What the public think

As the public are ultimate paymasters and users of the welfare state, no reform is likely to succeed if it does not align with what the public are happy with.[xi] What voters are likely to find acceptable is going to be driven by their preferences for risk, levels of concern about insecurity, ideas of ‘justice’, the extent of their desire for solidarity, fears about cost and finally any personal (or family) experiences of interacting with the current system. Unfortunately, there appears to be a paucity of up-to-date research data on the balance of these factors among the public and even less evidence of thinking about how such preferences might translate into policies towards welfare reform.

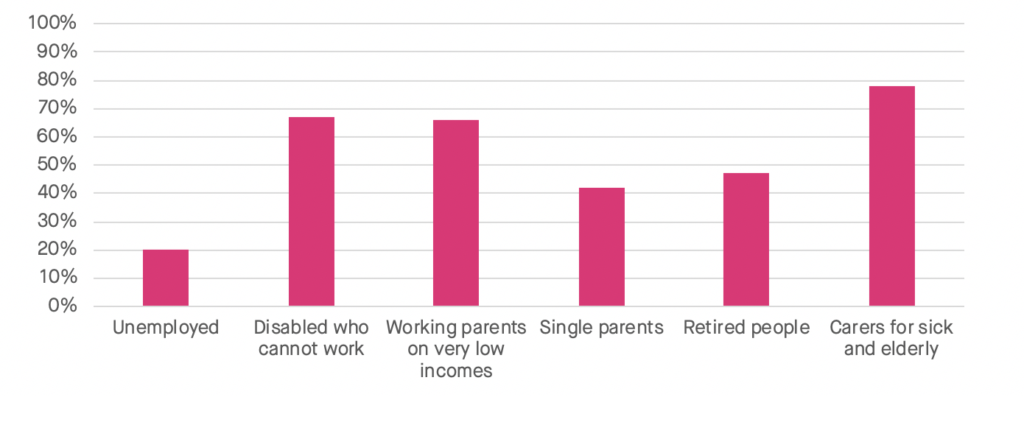

Perhaps the best available data is provided by through the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey. It collects data on public attitudes about welfare issues. However, these tend to be focussed on the allocation of welfare expenditure in the present or near future. Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the kinds of questions asked in BSA 35 about welfare.[xii]

Figure 3: Groups on which more welfare money should be spent

Source: British Social Attitudes survey, 2017

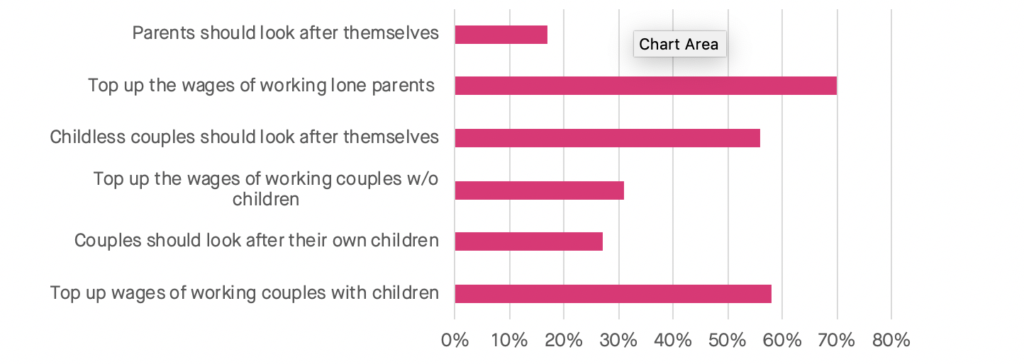

Figure 4: Role of the welfare state in supporting the low paid

Source: British Social Attitudes survey, 2017

While the nature of the questions posed to respondents about the focus of expenditure in the present are important, there is little in the BSA survey that attempts to identify the fundamental underlying values of the public towards and feelings about:

- The need for a welfare state, its overall construction and how consistent its current arrangement is with peoples’ preferences.

- Whether reform might be needed to adapt to emerging trends that are predicted to put considerable pressure on the current system. And if so, what principles might inform those reforms.

If there is to be reform – and it seems that in the medium-to-long-term the imperative to do so will prove impossible to ignore – in order for the re-design of the welfare state to be durable, it needs to reflect a public consensus about the values the system should embody.[xiii] In order to ascertain sufficient understanding of what the public thinks and believes about welfare and the underlying preferences that drive those beliefs, considerable research with the public would be needed. That research would need to enable the answering of a series of key questions if it is to help deliver the extensive understanding of the public that will be needed so that a new welfare settlement can be found. Those questions include the following:

- What is the best way to pool economic and social risk? Is it through the state on a pay-as-you-go basis, some form of state run-insurance system, social insurance funds or private provision or indeed, should there be any significant risk-pooling at all?

- Should expenditure be based upon the idea of ‘something-for-something’ (e.g. efforts to find work or a track record of tax-payments from a history of working) rather than ‘something-for-nothing’. In other words, whether welfare entitlement is ‘rights’ or ‘reciprocity’ based? What is the role of citizenship in this dichotomy?

- Do people prefer ‘universalist’ or ‘means-tested’ benefits and services, or a ‘needs-based’ approach? If a mixture, what should the balance be?

- What do the public think of the current range of ‘solutions’ to long-term welfare challenges being talked about in policy circles i.e. UBI, UJG and UBS?

- To what extent are taxpayers willing to pay the costs to reform the welfare state in their preferred way(s)? And if not, what kind of welfare provision can they have for the amount they’re willing to pay?

There will be, of course, empirical evidence both from the UK and around the world about the success or otherwise of different historical and contemporary approaches to welfare provision. All of which needs to be included in the debate over any future welfare reform and used to inform the public discourse in-particular. However, starting with the ambition to reform the welfare state informed by the public’s preferences is the right, indeed only realistic, starting place.

Getting started

Time waits for no-one, least of all politicians and policymakers. The sooner a debate about an issue can be started up and progress made in identifying what needs to be done the better. Efforts need to be made as soon as possible to fill the gaps in the evidence-base on what the public would like to see regarding structural welfare reform, in the face of the emerging demographic and economic trends of advanced capitalism as well as the controversies and failures of recent policies.

[i] The 2015 budget, in which the ‘freeze’ was announced, was a policy aimed at helping the government to save £12 billion from the working-age welfare budget by 2019-20. Specific measures not only included the freezing working-age benefits and Local Housing Allowances for 4 years but also reducing rents in social housing by 1% a year for 4 years and reducing the benefit cap. Source: HMT. (2015). Policy Paper: Summer Budget 2015.

[ii] In his book, The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Gosta Esping-Andersen identifed three models of welfare-state: ‘liberal’, ‘Conservative’ (or Corporatist) and ‘Social Democratic’. Each typology had a set of characteristics that made it distinct from the other two kinds, along dimensions such as ‘de-commodification’, extent of ‘social rights’, approach to the family and market orientation, among others. Source: Esping-Anderson, G. (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism.

[iii] The OBR estimates that between financial year 2018-19 and 2023-24 welfare spending will rise – in real terms – by more than £13 billion. Source: OBR. (2019). Welfare Trends Report.

[iv] Cheetham, M., Moffatt, S and Addison, M. (2018). The impact of the roll out of Universal Credit in two North East England localities: a qualitative study.

[v] Gugushvili, D and Hirsch, D. (2014). Means-testing or Universalism: what strategies best address poverty?

[vi] The ratio shows highlights how many people there is of pensionable age and over per 1,000 people aged 16 years to State Pension age (SPA). Forecasts project the expected future trend in this ratio. Source: ONS. (2019). Living longer and old-age dependency – what does the future hold? Examining the relationship between population ageing, economic dependency and international migration in the UK.

[vii] Frey, C B and Osborne, M A. (2013). The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerisation.

[viii] Degryse, C. (2016). Digitalisation of the economy and its impacts on labour markets.

[ix] Schwab, K. (2016). The Fourth Industrial Revolution: what it means, how to respond.

[x] World Economic Forum. (2018). The Future of Jobs Report 2018.

[xi] Muers, S. (2018). Culture, Values and Public Policy.

[xii] NatCen Social Research. (2017) British Social Attitudes 35: Work and Welfare.

[xiii] Muers, S. (2018). Culture, Values and Public Policy.