One of the most dramatic economic developments over the past 40 years, has been the declining power and influence of trade unions.

In many Western economies, unions have waned as a force for securing better pay and working conditions for employees. In 1979, some 13.2 million people in Britain were members of trade unions. By 2018 there were just 6.01 million members – a decline of over 50%.

The decline of trade unionism reflects a range of factors. Political reforms in the 1980s reduced the power and influence of unions. This includes privatisations; the opening up of industries to competition limited the ability of unions to use industrial action to achieve pay rises. Globalisation too has reduced trade union power, as firms have increasingly become able to relocate to other countries where worker rights are more limited. Technological change, coupled with the rise of the gig economy and ability to replace workers with robots, further threatens to curtail the ability of employees to have collective bargaining power.

This has left modern trade unions greatly weakened and limited in influence. Further, trade unions’ focus of attention has shifted as their membership has changed. Today, many unions are are largely focused on protecting the pay and working conditions of relatively well-paid public servants – rather than the poorest in society.

In 2018, over half (52.5%) of employees in the UK public sector were trade union members, compared with 13.2% of workers in the private sector. In the hospitality and retail sectors, where low pay is particularly prevalent, trade union membership is even lower, at 3.3% and 11.9% respectively.

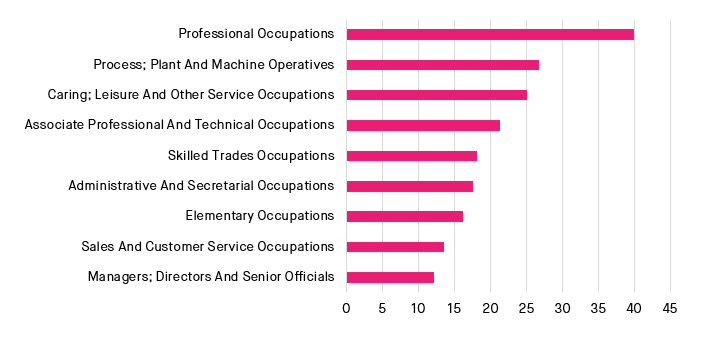

Unionisation rates are about 40% for those working in professional occupations, compared with 13.5% for those working in lower paying sales & customer services occupations. That is to say, unions are currently doing a poor job improving the living standards of those on the lowest incomes in society; or at least, unions are not, on the whole, representing those who might benefit the most from an increase in their wage-bargaining power.

Figure 1 Trade union membership as a proportion of employees by major occupation group, 2018, %

Source: BEIS

This is a pity, given the benefits that trade unionism, done right, can bring.

There is a growing academic debate, particularly in the US, around the extent to which labour markets have become increasingly “monopsonistic”, with employees being wage-takers rather than wage-setters due to their limited bargaining power.[1] Under monopsony conditions, workers can end up being paid below a fair market rate for their work, reflecting weak employee bargaining power.

Done right, a modernised trade union movement could restore the balance of bargaining power between employees and employers in our economy, supporting pay and better working conditions. Recent evidence shows that trade unions can provide an effective counter to monopsony power and support higher rates of staff pay.[2]

In the UK, trade union membership has been found to result in a pay premium for workers in the range of 10-15%.[3] There is also evidence that falling rates of unionisation and collective bargaining have resulted in wages becoming more dispersed and differentiated across occupations and locations.[4]

Recent Bank of England analysis suggests that declining unionisation rates in the UK have lowered wage growth by around 0.75 percentage points per year over the past 30 years[5]. To put this into context, if wage growth in the UK between 2000 and 2018 had been 0.75 percentage points per annum higher, average workers’ salaries would be about £3,800 (14%) greater.[6] That is to say, unionisation could significantly improve living standards and tackle low pay in the UK.

Politically, the future of trade unions should be an important topic. The Labour Party, mulling over its fourth consecutive general election loss, might reflect on the relative weakness of its trade union allies in delivering for people in greatest economic need. Could Labour drive a new approach to trade unionism that gives unions more relevance in the economy of 21st Century Britain? That new approach could include playing a role in broadening the services offered by trade unions, with a greater focus on education, training and skilling workers so they can benefit from career progression and also career change (for example, to overcome threats posed by automation).

A revived trade union movement also needs to reach out and support the many low-paid workers in relatively un-unionised parts of the economy such as retail and hospitality. If trade unionism becomes the preserve of professionals in the public sector, it risks fading into increasing irrelevance. The movement needs to build on recent developments aimed at improving collective bargaining among the low-paid – such as the formation of the Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain (IWGB) in 2012. IWGB represents mainly low paid migrant workers, such as outsourced cleaners and security guards, workers in the so-called “gig economy”, such as bicycle couriers and Uber drivers, and foster care workers. IWGB had about 2,500 members in 2018.[7]

Trade unions helped found the Labour Party and some remain affiliated to it. But Labour is not the only party with an interest in the issues of wage progression and wage bargaining. The Conservative Government owes its majority to the votes of people who previously voted Labour and who live in areas where unionised workers were once the norm. Much emerging Government policy is devoted to improving the economic conditions of such people and places.

Could trade unions play a part in the Conservative mission to help “left behind” places catch up?

There might indeed be political mileage in a more constructive Conservative relationship with trade unions. Survey research shows that most members of the public see unions as essential for protecting worker rights.[8] This suggests that a strictly “anti-union” world view might not resonate with much of the electorate, including the Conservative Party’s newfound supporters in the North of England.

Some within the Party already recognise this. Union Blue (the Conservative Workers & Trade Unionists), founded by Robert Halfon MP in 2015, notes that “moderate unionism” can play a key role in Conservative economic policymaking. The group’s starting premise is that “there should be a constructive working relationship between the Conservatives and trade unions.”

Halfon is, at the time of writing, a backbench MP and his ideas on Conservatives and trade unions are not his party’s official position. Could that change? With Boris Johnson looking for ways of levelling up the UK’s regions, and spreading higher incomes across the country, opening up a constructive dialogue with unions could make a lot of sense. Time for “beer and sandwiches” in Number 10? [9]

[1] See, for example, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/20161025_monopsony_labor_mrkt_cea.pdf

[2] http://personal.lse.ac.uk/tenreyro/monopsony.pdf

[3] Bryson, A (2014), ‘Union wage effects’, article for IZA World of Labor

[4] Gregg, P, Machin, S and Fernandez-Salgado, M (2014), ‘Real Wages and Unemployment in the Big Squeeze’, The Economic Journal, Vol. 123, pp. 403-432.

[5] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2018/pay-power-speech-by-andy-haldane

[6] SMF calculations using ONS labour market statistics

[7] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/jul/01/union-beating-gig-economy-giants-iwgb-zero-hours-workers

[8] https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/attitudes-trade-unions-1975-2014