Low income households pay a poverty premium for everyday essentials, including food, credit, energy and insurance, as the SMF has detailed in previous reports.[i] In this blog we are focusing on aspects of the poverty premium in insurance, particularly in relation to the additional costs imposed by society on poorer consumers. (We are not discussing here switching behaviours or payment behaviours). Overall, the insurance market helps consumers to manage risks and uncertainty and improves social welfare. For example, the main earner of a family can buy life insurance to ensure that dependents are financially secure if that earner passes away. Home insurance provides cover for losses or damages caused by accidents, disasters or incidents such as burglaries. However, we are concerned about the poverty premium paid by low income consumers for insurance.

The private insurance market operates in a way that incentivises consumers to minimise risks. Consumers incur a premium which is caused by a range of factors, and they can change their behaviour to lessen the risks associated with these factors. A homeowner might for instance improve the security of their home to reduce the chances of being burgled, whilst a car owner may drive more carefully to build a ‘no-claims bonus’. The possibility of such rewards is one of the main benefits of a private insurance market.

However, some of the factors that help determine risks are not within the consumer’s control. Here, the logic for forcing consumers to manage these risks rather than society doing so is much less clear.

This is where a poverty premium in insurance arises. Living in a deprived area with a high crime rate leads to an increased premium for household and motor insurance, as insurers set premiums to reflect the increased risk of a claim. This increased risk is often the fault not of the individual (who may be unable to afford to live in a more secure area), but rather of society to provide a safe environment. Ultimately, consumers are paying for the failure of law enforcement, and those on low incomes are disproportionately bearing this cost.

The poverty premium in insurance: its costs and prevalence

Studies show that consumers living in deprived areas pay a significant premium for their insurance. In 2007, Save the Children found a difference of £150 on home contents insurance and £100 on car insurance per year between deprived areas and affluent areas.[ii] A study from the OFT in 2010 found that both home and car insurance for the same consumer costs nearly a third more in Bow than in Chiswick.[iii]

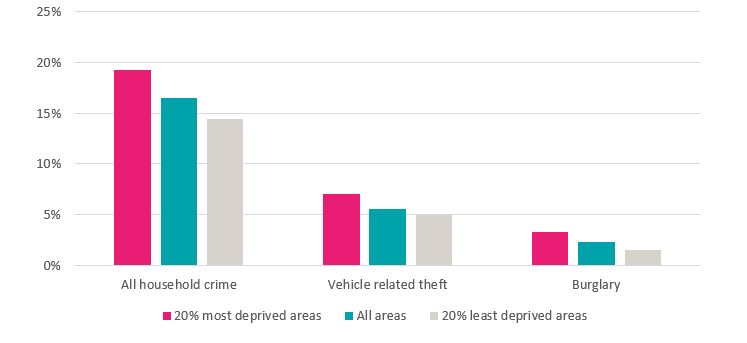

So, why do low income consumers have to pay more? A main reason is that they are more likely to live in deprived areas[iv], which tend to have higher crime rates.[v] The poverty rate in the most deprived local authority areas is almost double of that in the least deprived areas.[vi] The risk of being a victim of any household crime is higher for households living in the most deprived areas (19%) compared with those in the least deprived areas in England (14%). In addition, consumers in the most deprived areas are twice as likely to be burgled as those in the least deprived areas. These consumers incur a higher insurance premium, due to the higher risk of having their car or home burgled. This is despite the fact that low-income consumers may only be able to afford to live in more deprived areas.

Figure 1: Risk of crime by level of deprivation in England

The price is also based on previous claims history in the area – for example with car insurance, if there have been many crashes in the past, the insurers expect the risk of future crashes in that location to be higher. Urban locations tend to have more claims[vii], as more densely populated areas are likely to have more accidents, and these areas have higher levels of deprivation.

Given these facts, nearly three-quarters of low income households, who tend to live in deprived areas, incur premiums related to where they live.[viii]

Research has shown that 20% of the poverty premium is accounted for by area-based premiums, which is the second largest share after energy-related premiums.[ix]

The wider implications

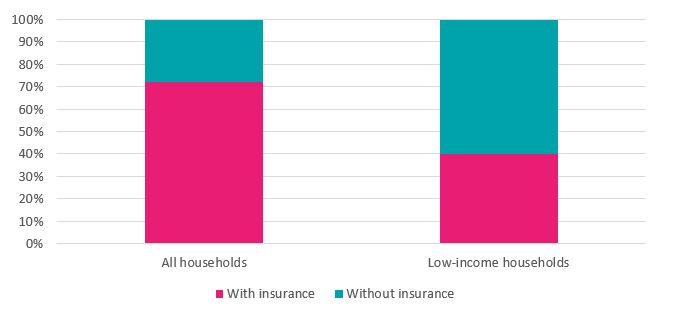

Low-income consumers pay more and these higher costs also probably contribute to under-insurance, where consumers do not have adequate cover. Evidence shows that lower income households have higher rates of under-insurance, yet they tend to face higher rates of loss.[x] The Financial Inclusion Commission found that 60% of those on low incomes do not have home contents insurance,[xi] far above the 28% rate for the whole population.[xii] It is important that low income consumers have insurance coverage to provide more security as they face a higher incidence of losses. Replacing or repairing items can cut into important savings, or the only option may be to use high cost credit.

Figure 2: Percentage of households with home contents insurance (2017)

This under-insurance arises for both demand and supply side reasons. Low income consumers may have behavioural biases and little trust of insurance products, as well as issues with affordability. On the supply side, complex products, pricing and a lack of transparency can create barriers for consumers.[xiii] If the insurance poverty premium was reduced to become more affordable, this could encourage take up of insurance products.

Who should bear the cost?

Although outcomes for low income consumer may not be optimal, we recognise that insurance pricing needs to consider different factors to assess the likelihood of a claim – we do not see this as a market failure of insurance. Some areas may genuinely be higher risk, and this should be reflected in the price. However, it does not seem reasonable to expect low income households to bear this cost, as living in a certain area is not within their control. Ultimately, consumers are paying for the failure of law enforcement, and those on low incomes are disproportionately bearing this cost.

This raises the question of how the costs of this social failure should be paid for more equitably.

There are some existing examples of interventions in insurance pricing, such as the UK government backed “Flood Re” scheme, which is funded by a levy on insurers.

Flood Re scheme

This is a government backed scheme that was created to provide affordable, discounted flood insurance to households in high-risk flood areas. It is funded by insurers paying a levy into the “Flood Re” scheme, which is used to cover flood risks in home insurance policies. Essentially, this cost gets passed onto all policyholders.

The insurer offers a lower price for the flood part of their insurance, and prices the remaining according to other relevant factors.[xiv] As with other insurance cover, there is a moral hazard risk – households may not be incentivised to reduce the likelihood of being flooded or take measures to reduce any damage.

Flood Re is due to be phased out by 2039, by which time a risk-reflective market for household flood insurance is expected to exist.

In Ontario, Canada a cross-party group of legislators in the provincial assembly has proposed eliminating area-based premiums, which they refer to as “postal code discrimination” against residents of Toronto, the provincial capital.[xv] Last autumn, a bill was proposed to remove location from the determination of car insurance premiums, and basing it on driving record instead. However, this was voted down.[xvi]

We have considered two broad options for how the area-based poverty premium could be addressed.

1.Remove location from determining home and car insurance premiums (excluding flood protection)?

Location could be removed from determining home and car insurance premiums (excluding flood protection). If regulators did not allow insurers to factor in location to their pricing of home and car insurance, low income consumers would not be penalised for living in more deprived areas. Instead, the premium could be determined largely by factors that the consumer can influence, such as their driving record – as has been suggested in Ontario.

If this was introduced, insurers would be likely to increase costs to all consumers to account for this. This outcome could be more equitable than the costs falling disproportionately on low income consumers. The levy imposed by Flood Re leads to increased costs for all policyholders, who are incurring a higher cost on behalf of those who are living on flood plains. It appears reasonable to extend this to low income consumers who live in deprived areas. We note that, looking to examples outside of insurance, the “green levies” in energy markets have been unpopular. The energy efficiency obligations on suppliers has filtered through to consumers, and there have been calls to reduce this.[xvii]

2. State subsidy to address the additional premium caused by higher risk locations?

An alternative option is for the government to introduce a subsidy payment to low income consumers to cover this cost. Ultimately, it is the duty of the state to protect the safety of the population. There has been a failure of this in areas with high crime rates, which low income consumers are disproportionately paying for. As much of police funding is determined centrally, the national government should be best placed to bear this cost. Funding this subsidy through taxation is more progressive[xviii], although it would be difficult to implement.

Conclusion

Poverty premiums are unfair and harmful: they erode trust in markets and support narratives suggesting the system is unfairly rigged against those on lower incomes. Area-based premiums in insurance largely reflect not the conduct of individual consumers but wider social factors which they cannot control, especially the local crime rate. Requiring low-income consumers to bear the cost of that elevated risk is not reasonable and is likely to fuel those narratives of unfairness. As such, it is in the interests of the insurance industry and politicians across the spectrum to address it. Both the options we outline above have downsides and costs that would have to be considered carefully and spelled out clearly before proceeding. Alternatively, if policymakers wish to address this issue without tackling those downsides and costs, they have another option: better policing and crime reduction in low-income areas.

[i] See for example, SMF, Measuring the Poverty Premium (2018); Sara Davies, Andrea Finney and Yvette Hartfree, Paying to be poor: uncovering the scale and nature of the poverty premium, (University of Bristol, 2016)

[ii] Save the Children and Family Welfare Association, The poverty premium: How poor households pay more for essential goods and services (2007)

[iii] OFT, Europe Economics and New Policy Institute, Markets and Households on Low Incomes (2010)

[iv] Cabinet Office, Improving the prospects of people living in areas of multiple deprivation in England (2005)

[v] Dean, Hartley and Platt, Lucinda, Social Advantage and Disadvantage, Oxford University Press, pp. 322-340 (2016)

[vi] IFS, Living standards, poverty and inequality in the UK: 2017–18 to 2021–22 (2017)

[vii] https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2018/aug/half-london-car-crashes-take-place-5-citys-junctions

[viii] Sara Davies, Andrea Finney and Yvette Hartfree, Paying to be poor: Uncovering the scale and nature of the poverty premium (University of Bristol, 2016)

[ix] Sara Davies, Andrea Finney and Yvette Hartfree, Paying to be poor: Uncovering the scale and nature of the poverty premium (University of Bristol, 2016)

[x] Financial Inclusion Commission, Improving access to household insurance (2017)

[xi] Financial Inclusion Commission, Improving access to household insurance (2017)

[xii] https://www.abi.org.uk/news/news-articles/2019/01/cost-of-home-contents-insurance-falls-to-a-record-low-yet-one-in-four-uk-households-are-uninsured/

[xiii] Financial Inclusion Commission, Improving the financial health of the nation (2017)

[xiv] HTTPS://WWW.ABI.ORG.UK/PRODUCTS-AND-ISSUES/TOPICS-AND-ISSUES/FLOOD-RE/FLOOD-RE-EXPLAINED/

[xv]https://www.ctvnews.ca/autos/ontario-private-member-s-bills-aim-to-end-auto-insurance-postal-code-discrimination-1.4135249

[xvi]https://www.lowestrates.ca/news/bill-end-postal-code-discrimination-ontario-defeated-25360

[xvii] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/personalfinance/energy-bills/11362064/Green-levies-add-112-to-energy-bills-where-does-the-money-go.html

[xviii] See for example, Alan J. Auerbach, The choice between income and consumption taxes: a primer (2006)