Since the 1940s Britain’s party system has steadily undergone a fragmentation away from the main political parties. This trend was displayed most starkly in the 2015 General Election, where a substantial share of the vote went to several smaller parties – the SNP, UKIP, the Greens, and Plaid Cymru.

In our ESRC-sponsored Chalk + Talk event, the SMF hosted Professor Edward Fieldhouse of the Institute for Social Change, University of Manchester who presented explanations for the fragmentation of Britain’s political party system. His analysis draws on his work as Director of the British Election Study.

Long term decline of the two-party system

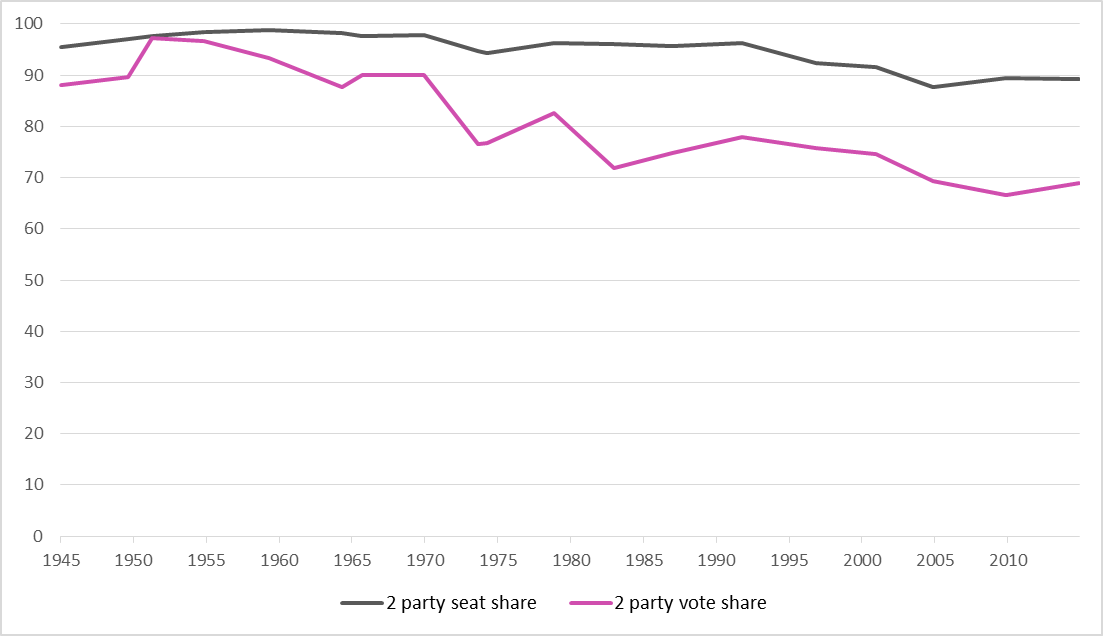

The vote share of the two main parties has been in decline for several decades. In General Elections during the 1950s over 90% of votes went to either Labour or the Conservatives. But by 2005, this had fallen below 70%. This falling vote share has, to an extent, translated into fewer seats for the two main parties, although Britain’s First Past the Post electoral system advantages larger parties, lessening the severity of the trend.

Figure 1: Share of votes and seats going to the two main political parties

Note: Source of all charts is British Election Study

But why did this long-term trend towards fragmentation lead to a dramatic increase in the vote share of several smaller parties in the last General Election? This is primarily due to three key factors.

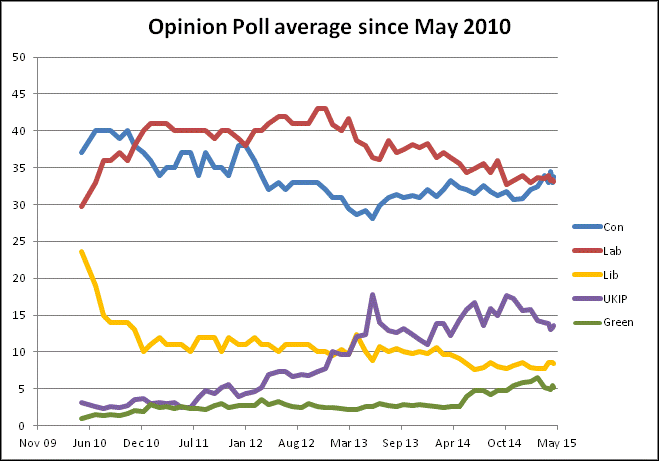

1. Collapse of the Liberal Democrats

The vote share going to the two main parties in the last election was not substantially lower than the long term trend would suggest, at around 70%. The big difference was the collapse in support for the third party. The falling popularity of the Liberal Democrats can be attributed to a variety of events, but the most significant appears to be the forming of a Coalition with the Conservatives. As shown below, most of the fall in popularity came immediately after the 2010 General Election, once the Coalition Government had been announced (and before other important events such as the tuition fees vote).

Figure 2: The decline in Lib Dem fortunes is visible long before the tuition fees vote in December 2010

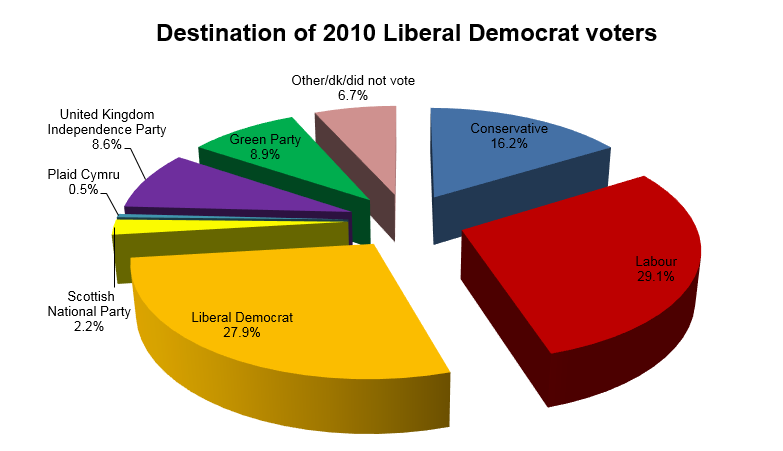

In the 2015 election the Liberal Democrats managed to keep hold of less than 30% of their 2010 supporters, with by far the largest number of defectors voting for Labour. However, rather than helping Labour, this appeared to be of most help for the Conservatives, since the Tories were the main challenger in many former Lib Dem seats. Disillusioned Liberal Democrat voters defecting to Labour simply allowed the Tories to win these seats.

But many voters also turned to the smaller parties – including the Green Party, UKIP, the SNP and Plaid Cymru.

Figure 3: Destination of 2010 Liberal Democrat voters in 2015

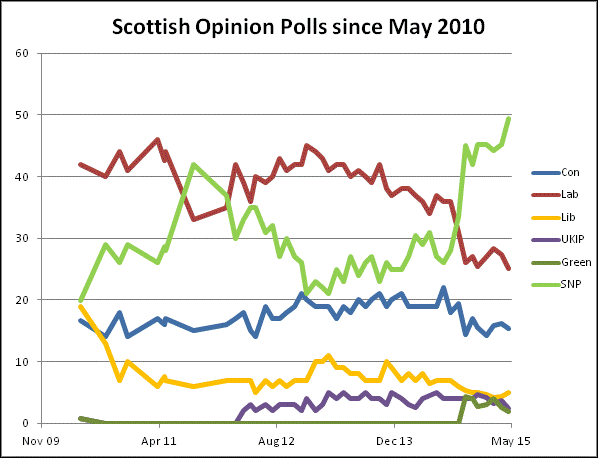

2. The impact of the Scottish Independence Referendum on the SNP

Another major story of the 2015 General Election was the dominance of the SNP in Scotland. The huge rise in support can largely be traced to the referendum on Scottish independence, during which Labour support – perhaps driven by joint campaigning with the Conservatives – dropped substantially. The SNP were able to retain a huge 90% of those voting Yes in the referendum as supporters during the General Election, whilst also finding support amongst some of those voting No.

Figure 4: Polling of parties on Scotland since May 2010

3. Expectations of a hung Parliament

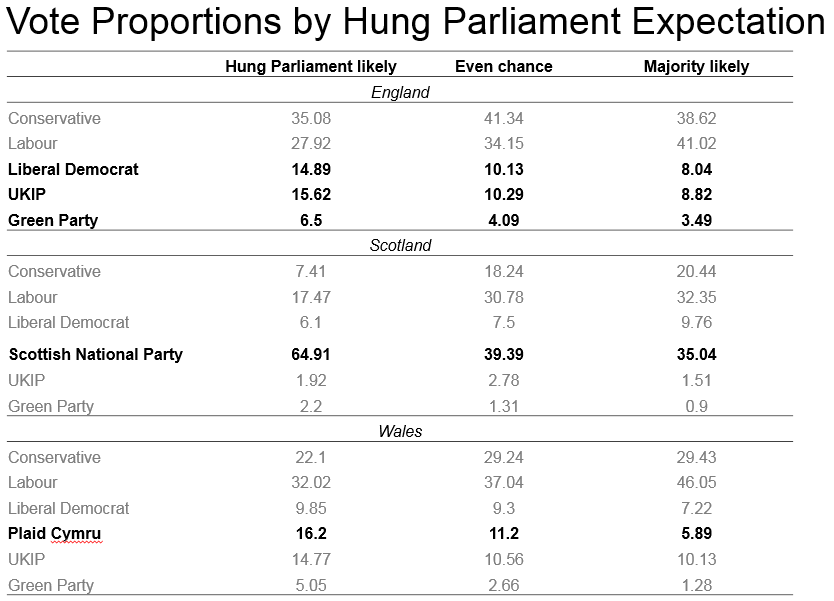

But a third key factor in driving fragmentation was the expectation of a hung Parliament. This expectation changed voters’ ‘normal’ calculations about which party to vote for by increasing the likelihood of small parties having influence as part of a coalition government. It also decreased the utility of ‘tactical voting’ and increased the likelihood of ‘sincere’ voting, in the face of considerable uncertainty around the result, and a lack of an unambiguous choice between potential governments.

The importance of the expectation of a hung Parliament is demonstrated by differences in the incidence of voting for smaller parties between those thinking a hung Parliament likely, and those thing it unlikely, as shown below. Those predicting a hung Parliament were substantially more likely to vote for the Liberal Democrats, UKIP or the Green Party in England; for the SNP in Scotland; and for Plaid Cymru in Wales. Furthermore, modelling results show that this correlation is not simply because those voting for small parties also happened to think a hung Parliament more likely: perceptions of a likely hung Parliament appeared to be driving small party voting.

Figure 5: Vote proportions by hung Parliament expectation

The 2015 General Election was therefore not only part of a longer-term trend towards a decreased vote share for the two main parties, but also displayed a fragmentation of the remaining vote between several smaller parties. This fragmentation was driven by three factors: the collapse of the Liberal Democrats; the huge gains made by the SNP during the referendum, along with their ability to retain the vast majority of this support; and the expectation of a hung Parliament giving voters greater motivation to move away from the mainstream.

You can listen to a podcast of this Chalk + Talk session below:

—

Chalk + Talk is the SMF’s popular lunchtime seminar series, run in partnership with the ESRC. Chalk + Talk brings the best policy output from the world of academia into the heart of Westminster.