Despite its medicinal and economic potential, regulatory constraints and outdated political views are hindering the impact of CBD. In this blog, Jake Shepherd, SMF Researcher, discusses the emerging CBD market and what the current regulatory landscape means for hemp farmers, consumers, and the industry as a whole.

Cannabidiol (CBD) is a compound that belongs to cannabis plants. It is just one of over a hundred naturally occurring phytocannabinoids that, when consumed, produce pharmacological effects. The defining difference between CBD and its better known cannabinoid cousin, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), is that CBD does not create the ‘high’ cannabis is typically used for. CBD is legal, non-intoxicating, and does not cause harm.

CBD can be found in a wide range of food and healthcare products and is praised for its health and therapeutic benefits. Clinical studies have found it to be effective at treating epilepsy and spasticity, with CBD-based medicines for those conditions now available for prescription through the NHS. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has found there is “preliminary evidence” suggesting it could be used to treat other serious illnesses, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, and cancer. CBD is also said to help relieve anxiety, insomnia, and chronic pain, though the empirical evidence supporting these claims is inconclusive.

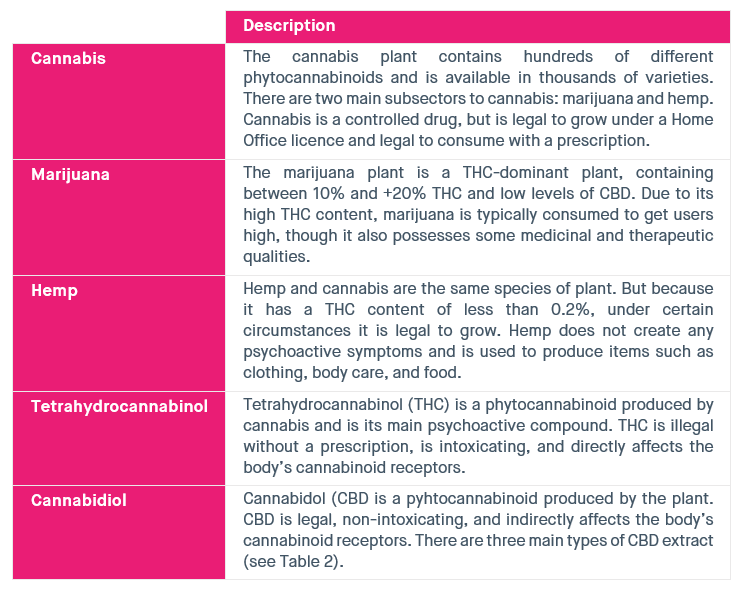

Table 1: Key cannabis terms

Source: SMF

In the context of increasingly popular consumer wellness trends, there is currently a lot of hype around CBD, as demonstrated by significant demand for CBD products. In 2021, the CBD industry was estimated to have generated £690 million in sales, and it is expected to be worth almost £1 billion by 2025. The UK’s sector is already the world’s second largest CBD market, behind that of the United States. Despite its medicinal and economic potential, regulatory constraints and outdated political views may be hindering the impact of CBD.

The regulatory landscape

Under consumer law, CBD is categorised as a ‘novel food’: a “food or food ingredient that has not been eaten to a significant degree by people within the EU or the UK prior to May 1997”. Novel foods cannot be placed on the market unless they are approved by the Foods Standard Agency (FSA), the reason being to ensure they do not present any harm to consumers, or mislead them. Novel foods include traditional foods eaten elsewhere in the world, for example chia seeds and insects, new foods, or foods produced from new processes.

It would be wrong to question the intent of a regulator looking to mitigate the potential negative impacts of consumer goods. But as drugs research and advocacy group, Volteface, has pointed out, the current regulatory framework does present some challenges for specialist UK CBD oil producing firms. For such products to enter the market, they must gain approval from the EU and be authorised by the UK government, imposing stringent ‘red tape’ and testing standards that small businesses are unable to adjust to. It has been claimed that, due to several technical problems arising from the FSA’s authorisation process, the regulation has “undermined the foundations of the very market it was seeking to legitimise”.

Charles Clowes is a director of the Cannabis Industry Council and Bud & Tender, a specialist CBD supplement company. Citing a report by the All Party Parliamentary Group on CBD Products, he says the application process for achieving novel food status is complex, costly, and flawed. He argues that due to the amount of money needed for farmers just to produce a test sample for the FSA – around £20-30 million to cover infrastructure, production, and licensing costs – before an authorisation assessment is even made, there is little to no domestic farming of hemp for CBD products. Currently, almost all are imported from abroad, from countries such as the US, Switzerland, China, and from Europe.

According to Clowes, novel foods regulation makes the CBD industry anti-competitive. The same APPG report points to the huge costs involved in making an application, as well as restrictive licensing laws that do not allow UK farmers to harvest the flowing tops of hemp plants to extract CBD, meaning small hemp farmers are excluded from entering the sector. As such, there is “no possibility” that an innovative UK hemp CBD industry can be established. As it stands, only large corporations have the capital, resource, and infrastructure needed to submit applications to the FSA, running the risk of monopolisation. What’s more, many start-ups have found themselves confused by the FSA’s rules, pushing companies – both those selling poor quality, “cowboy products” and companies with better quality products – out of the market.

Recommendations made by the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) may further hamper the UK’s CBD industry. Under the proposal to limit the THC content of products to 50 µg per unit – much less than what is naturally found in the hemp plant and less than the established limits of Canada, Switzerland, Jersey, and the United States – it will be even more difficult for farmers to enter the market. It is argued these changes will continue to stifle the production of natural, plant-based products and steer the industry towards synthetic CBD created in labs. This is likely to increase the risk of influence from large pharmaceutical firms and create a concentrated market with less effective products.

Despite being a legitimate product that is openly sold alongside many other food and healthcare products, CBD is subject to several regulatory constraints and ambiguities that affect producers, consumers, and market growth. Regulation should encourage market entrants and competition to drive innovative, better products and deliver better outcomes for customers, not curb them. As it stands, undue regulation means the CBD sector is not functioning quite as it should.

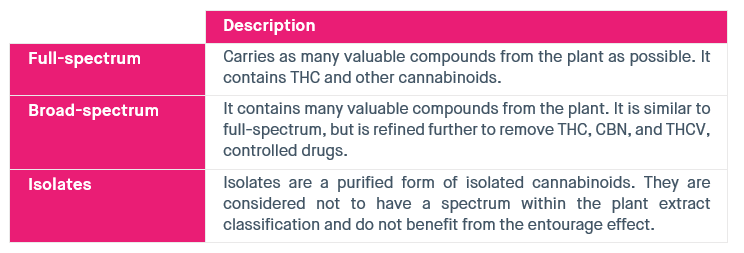

Table 2: Different types of CBD extract

Source: SMF

Outdated political views

Current regulation is restricting the growth of a strong and profitable agricultural CBD industry. Novel foods status and the complicated application process required to achieve it is shutting UK hemp farmers out of the market, risking the likelihood of corporate capture and monopolisation. Meanwhile, the ACMD’s plans to limit the THC content of CBD products, which favour large companies with the capacity to produce CBD artificially, may repel domestic growers further.

It is unlikely this would be an issue if cannabis was not prohibited. As described above, for any cannabis-based product to be placed on the market legally then THC must be extracted from it. In the UK, strict limits are imposed on CBD products; in countries with looser cannabis laws, THC limits for CBD products are higher. As for being categorised as a novel food, cannabis has been used by humans for medicinal purposes for thousands of years. CBD is hardly novel, and it does not have any abuse potential or cause harm. Under current regulation, CBD is more stringently controlled than that of the alcohol or tobacco industries, which make considerably more harmful products that are sold and purchased freely.

The full effects of CBD are not yet clear. It is established that CBD has plenty of medicinal potential, particularly with regards to serious conditions like epilepsy and maybe even cancer. But some of its other publicised benefits, such as managing anxiety, currently lack evidence. As it stands, not only is the UK missing out on the prospect of a flourishing hemp-based CBD market – the creation of farming jobs, exports, and capital – but it is also being prevented from advancing medical research. The scientific development of cannabinoids like CBD, with the aim of producing more effective cannabis products, is an endeavour which could significantly improve consumers’ health and wellbeing. It could also help the environment, as hemp is better at sequestering carbon than any other plant. If grown in the UK, CBD could support the Government’s decarbonisation plans.

Because of current prohibition laws and the taboo surrounding illicit substances, much of the discourse around cannabis – used for recreational purposes or otherwise – is unaccommodating for the development of cannabis-based products. If it, and its main psychoactive compound, THC, were not prohibited, then the regulation and development of the CBD industry would be much less thorny. This could be considered yet another shortcoming of the UK’s current prohibition regime. As CBD becomes legal across many of parts of Europe and demand continues to grow, there is a burgeoning international export industry ready to be tapped into. With a new regulatory framework – led by reformed drug laws – a valuable and long-term hemp industry could come into existence.