Housing Secretary Michael Gove has announced plans for increasing housing supply through changes to brownfield planning. Will these changes have an impact on Britain's chronic lack of housing? Senior Researcher Gideon Salutin digs into the details to find out.

If Secretary Michael Gove was aiming to turn the tables on Labour, his new housing plan has been underwhelming. After prodding No. 10 over the weekend, Gove announced on Tuesday a two-pronged housebuilding strategy aimed at increasing housing supply through changes to brownfield planning. The plan would push councils in England’s largest towns and cities to build on brownfield land when they fail to meet their housing targets and allow more former commercial buildings to be converted into flats.

New buildings are necessary to house Britain’s growing population, and for years we have failed to build enough of them. Planning reforms like these are floated as a way to increase the supply of homes and slow down any increase in housing prices. They are also often designed to bypass NIMBY activists who advocate against new housing in their area.

At present, if you are a local planner in England, builders come to you requesting permission to build on a specific lot. To check whether your area is building enough, you must report the number of homes developed in your local authority over three years to the central government, which then compares it to the amount which it calculates is required to meet population growth. If authorities are underdelivering, they may be forced to develop a new plan, allocate more land for housing, or ease application requirements depending on the size of the backlog.

Under Gove’s changes, local planners will be asked to be more flexible with applications for brownfield land, but not as a legal requirement. The only required change will come if you are a local planner in one of England’s 20 largest towns and cities and you deliver less than 95% of the homes required, in which case you will now be forced to allow development on brownfield sites subject to certain qualifications (more on that below).

But if you’re a local planner you probably shouldn’t be worried. In 2022, just four of those twenty towns and cities delivered less than 95% of their target, including Bristol (88%), Southampton (75%), Bradford (67%) and London, where seventeen of the city’s 33 local planning authorities under-delivered. That means that of England’s 287 local planning authorities, just 20 are affected by Gove’s housing plan.

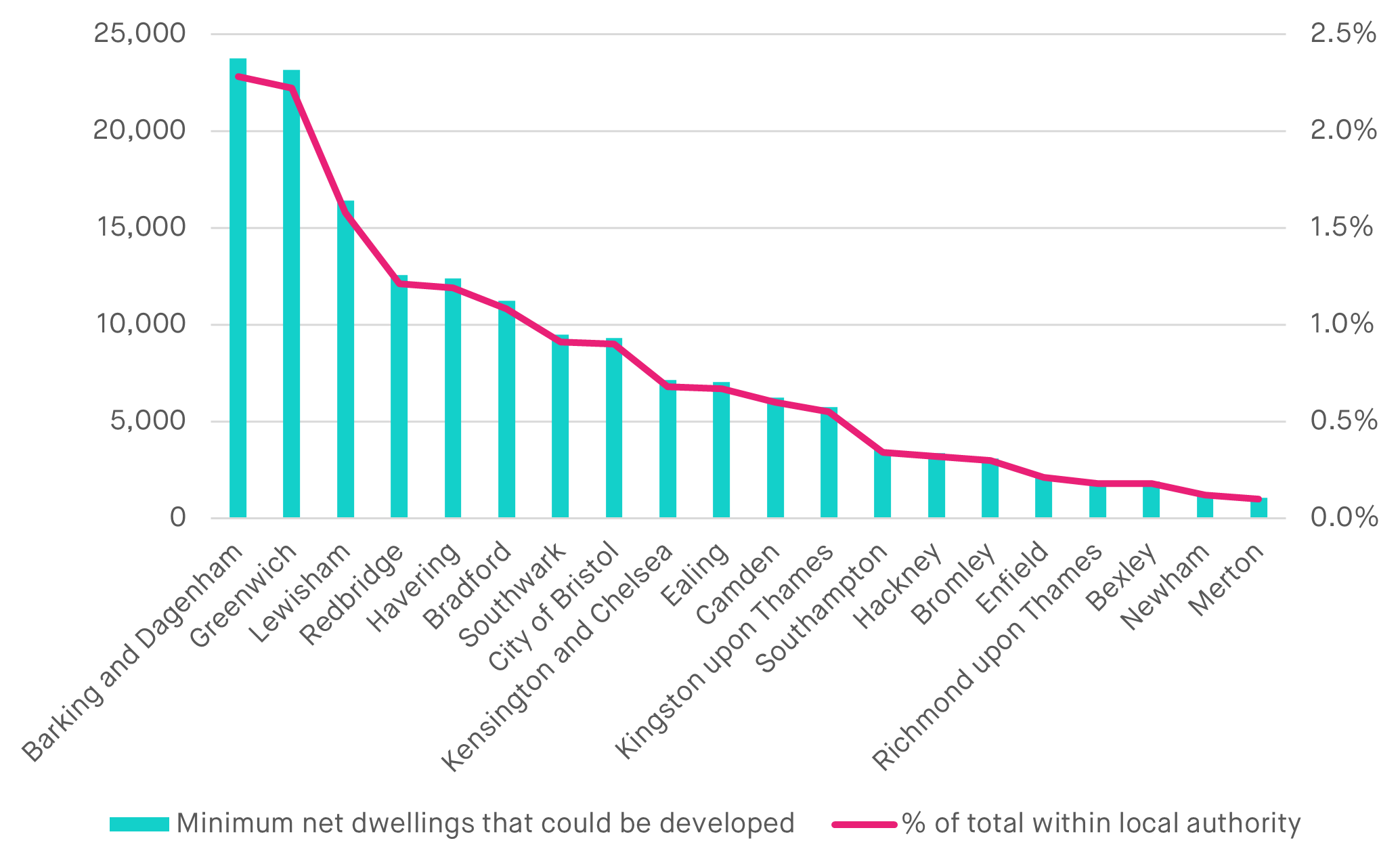

And within these authorities, the impact will barely be felt. Even if all brownfield sites are developed, the net impact on housing will be minimal. In 2019, the National Housing Federation surveyed local authorities asking the minimum net dwellings which could be developed on all existing brownfield sites. None of the authorities impacted by Gove’s plan have enough brownfield sites to reach their target. On average, Gove’s plan would increase housing stock in these towns and cities by 0.78%, and increase British housing stock by 0.5%.

Figure 1: Effect of Housing Secretary Michael Gove’s brownfield sites planning strategy to increase housebuilding

Source: SMF analysis; National Housing Federation

And that’s optimistic. Brownfields are not created equal, and Gove’s plan makes clear that the government “remains committed to the restrictive policies” which protect brownfield sites from development under certain conditions. This precludes greenbelt land, heritage assets, and another eight land categories that severely constrain builders. The government also makes clear that applications could be rejected to protect local “character and density,” two of the top objections NIMBY actors have raised to new residential housing.

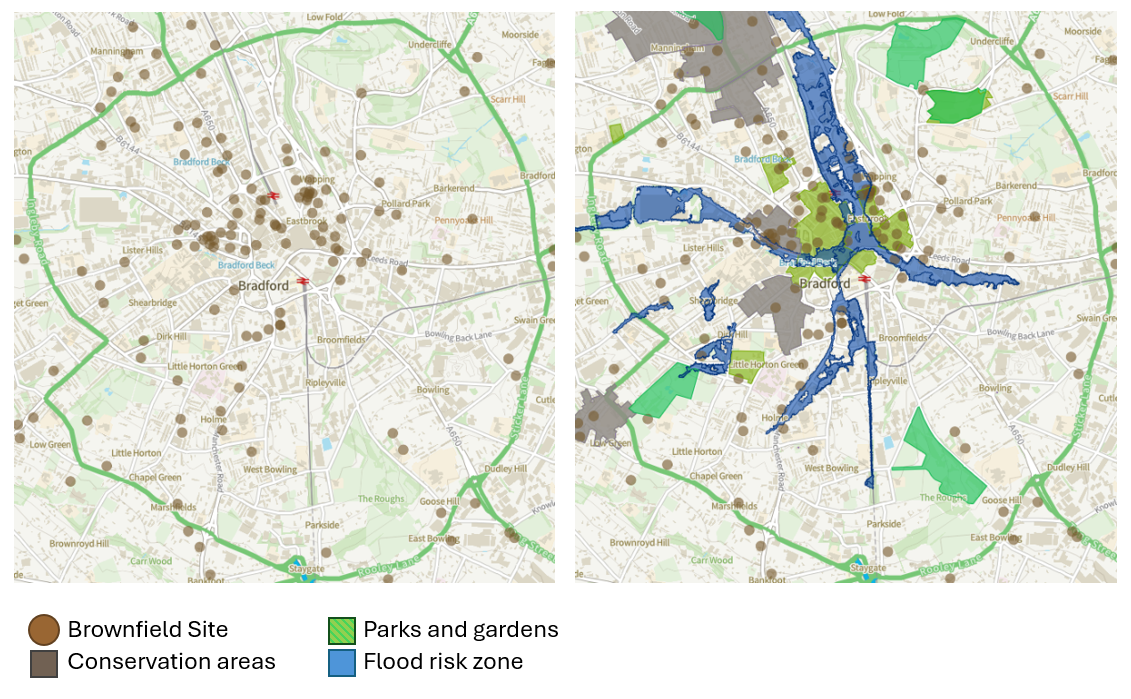

Take Bradford, which currently contains approximately sixty brownfield sites in its inner core. That number drops dramatically when you exclude sites that are at least partially within conservation areas, parks or gardens, and flood risk zones, all of which exempt them from the policy. This does not even take into account restrictions on ‘character’ and ‘density’, which could have any number of interpretations.

Figure 2: Central Bradford brownfield sites, before and after taking into account local area classifications

Source: DLUHC

Nor are office conversions likely to generate a boom in supply. Already most property owners have the right to convert their buildings to residential use for up to 1,500 square meters of floor space. Gove’s plan scraps that size limit, but conversions will still need to be approved by local planners. Meanwhile, property owners appear squeamish. In the year to September, 2,108 conversions to residential applications were accepted or not required by local authorities while 1,138 were rejected. It’s unclear how many of these were rejected for size restrictions, but these numbers are a drop in the bucket compared to the millions of homes needed to meet Britain’s housing backlog.

Building on brownfield land is a more politically palatable suggestion than building on the greenbelt, and is cheaper for the government than revitalizing council housing. That’s why leaders including Boris Johnson and Keir Starmer have already endorsed the prospect. But that doesn’t make it an effective policy or a proportionate response, and when it comes to planning reform the devil is often in the local details.

This blog draws on research conducted as part of our ‘What can the UK learn from other countries’ housing crises and policy?’, kindly funded by the Nuffield Foundation.