"A new tax credit deal must ensure any cuts are phased in gradually – but doing this can still give Osborne what he wants by 2020."

Following the Government’s defeat in the House of Lords over reforms to tax credits, George Osborne has promised to ‘lessen’ the impact of tax credit cuts by providing ‘transitional help’ to families. We will hear the details of these plans on the 25th November when the Chancellor gives his Spending Review – but what might these changes look like? Can the Chancellor genuinely protect families from the cuts, but still get what he wants? Here we look at some of the available options.

Cutting taxes and national insurance for low earners

One option is to compensate families with changes to tax allowances. The Chancellor has already argued that increases in the Personal Allowance can offset the cuts. The problem is that they don’t offset by nearly enough, and – as shown by the Resolution Foundation – are very expensive because they are poorly targeted. Someone earning £12,500 will see their income tax bill reduced by £380 a year by 2020; but these same savings also go to much higher earners, making the policy extremely expensive if the main concern is to protect those on low incomes.

Increases in the threshold for paying National Insurance, whilst slightly better targeted at low earners, suffer from similar shortcomings. Raising the threshold such that nobody earning under £10,600 pays NICs could lower a low paid employee’s NICs bill by around £300. But because many high earning employees would get the same benefit, the policy would cost around £6bn a year – far outweighing the £4.4bn benefit to the exchequer of cuts to tax credits.

Phasing in tax credit cuts

Another option would be to phase in tax credit cuts such that they only applied in full by 2020. This option has also been mooted elsewhere, but the exact figures are worth a closer look.

Phasing in wouldn’t just reduce the initial pain for families; but would also allow the full impact of increases to the minimum wage to be felt before feeling the full pain of the cuts. Of course it would cost the exchequer money, compared to the previous plans – but would likely cost much less than changing tax and national insurance thresholds, and would be much better targeted at low earners. The Chancellor’s deficit target is to ensure a surplus by 2019/20. We calculate that phasing in the tax credit cuts would leave the deficit only around £900m larger in 2019/20 than it would otherwise have been under the previous plans. And because on current OBR projections there will be a £10bn surplus in 2019/20, the Chancellor has some room for compromise whilst still hitting his surplus target.

What phasing in would mean for household incomes

There are two key mechanisms by which the Chancellor has proposed to cut tax credits: reducing the income threshold – the amount that can be earned with no tax credit withdrawal – from £6420 to £3850; and increasing the taper rate – the rate at which tax credits are withdrawn as income rises – from 41% to 48%. Here we suppose that Osborne’s plans are implemented in full by 2020. But in 2016, the taper rate increases only to 42.5%, with the threshold decreasing to just £5906. In 2017, the taper increases to 44% with the threshold decreasing to £5392 – and so on until the full extent of the cuts have been implemented in 2020-21.

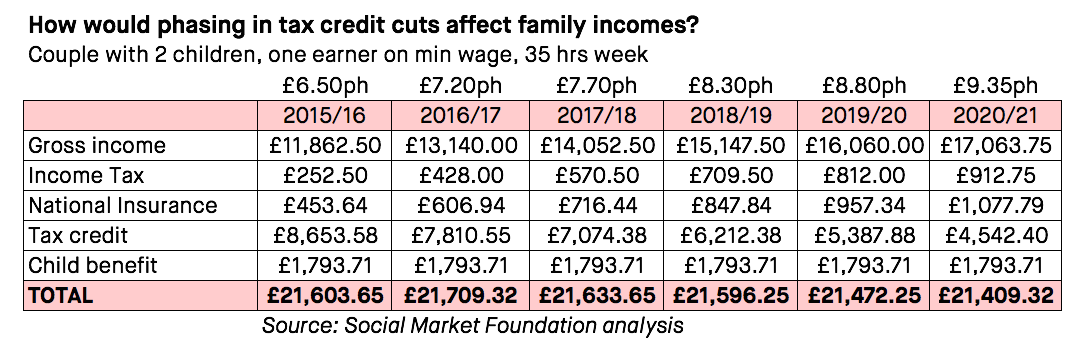

What would this phasing look like for household incomes? For a couple with two children, and with one earner working full-time on the minimum wage, nominal incomes would rise slightly in 2016/17, before falling gently each year until 2020/21. However, the maximum loss from peak to trough is just £300 – far less than the £1,290 reduction the same family would have seen in 2016 under the original proposals, and with a much smaller reduction from year to year.

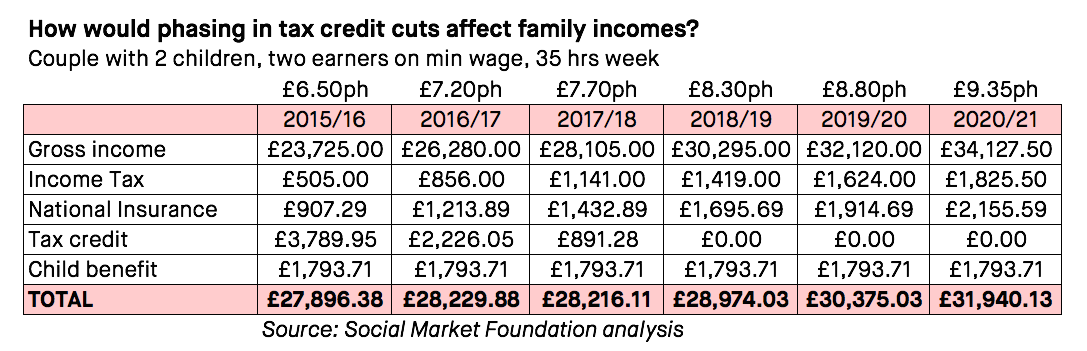

Alternatively, take a couple with two children, with both adults in full-time work on the minimum wage. This couple does relatively well because the minimum wage increase has a particularly large impact for two earner families. Their income rises nearly every year in nominal terms, and by 2020/21 they are better off even in real terms than they were in 2015/16 (assuming 2% annual inflation).

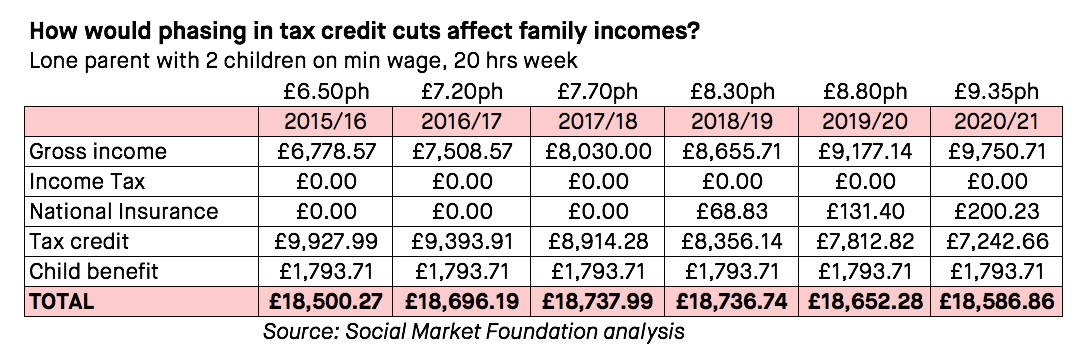

Lastly, we can look at how a lone parent, working 20 hours a week and with two children, would fare under these plans. Again, the changes in income are much more gradual from year to year, and income is higher in 2020, albeit only in nominal terms.

Of course, for many families these cuts will still leave them worse off in real terms. Those earning just above the minimum wage may not feel the impact of minimum wage increases. The government may therefore also reduce the overall scale of the cuts to ensure families do not lose out in real terms. In addition, it would be best to implement these reforms alongside other changes as well – for instance, in forthcoming work we document how the labour market can be reformed to help low earners. But whatever other options are chosen, the phasing in of tax credit cuts offers a much gentler transition to the ‘higher wage’ society the Chancellor wants than the proposals just thrown out by the Lords.

—

Notes:

All figures are in nominal terms. We’ve assumed maximum tax credit take-up, but no claiming of housing benefit or council tax support. We’ve also assumed the National Insurance threshold remains unchanged in nominal terms, and that the Income Tax Personal Allowance is raised to £11,000 in 2016/17, then gradually up to £12,500 by 2020/21. Our calculations assume families stay on the old tax credit system and do not move to Universal Credit.