The Chancellor has set himself a difficult target to run an overall surplus by 2019-20. Ahead of the Autumn Statement, SMF Chief Economist Nida Broughton looks at the options for Osborne and concludes that he will need to look at asset sales, reimagining the boundaries between departments, or making businesses and individuals pay for public services in other ways, in order to find the necessary additional savings to meet his budgetary target.

In two weeks’ time, the Chancellor will be setting out the spending cuts needed to meet his target of eliminating borrowing and running a surplus in 2019-20 – a historically rare feat. Some departments have already agreed 30% cuts to their budgets this Parliament. Outside the protected areas of health, education, defence and international development, other departments are likely to face similar levels of reductions in their budgets.

Finding savings is likely to be very difficult. Many areas of Government spending have already seen substantial cuts since 2010. Meanwhile, the Chancellor is under pressure to find ways of easing the pain to tax credit claimants, where cuts in generosity of benefits were due to save over £4 billion.

This has promoted suggestions that the Chancellor could ease up on his plans, for example, by “dipping into” his planned surplus. Back in July, the OBR forecast that if the Treasury’s planned spending cuts were put into action, George Osborne would overshoot his target to eliminate borrowing, and would run a surplus of £10 billion in 2019-20. That potentially leaves some room to reduce the severity of cuts. There are also some suggestions that the finances might be looking better than expected, meaning that fewer savings might need to be made.

So how easy is the job of setting out spending cuts looking? And is there room for some cuts to be cancelled?

We argue that the picture is looking mixed. It isn’t clear that the OBR is about to make some helpful revisions, and even if it does, the uncertainty of forecasts means that the Chancellor could easily end up having to pencil back in any cuts he cancels now. With the deficit target looking as challenging as ever, we argue that the Chancellor will need to fall back on asset sales, reimagining the boundaries between departments, and making businesses and individuals pay for public services in other ways.

The tax take is looking healthy, but spending needs to fall this year to meet forecasts

The latest figures show that tax revenues are looking healthy this year compared to original forecasts. In the first six months of this financial year, revenue has been around 4% higher than the same time last year, with VAT and corporation tax looking particularly strong.

But spending in number of areas has been higher in the first six months than the same time last year. Net investment is 11% higher, despite the fact that it is expected to finish the year around 6% lower. Current, non-investment, spending is also looking higher compared to full year forecasts. This all suggests that central government spending will have to be reined in over the last six months of 2015-16 to meet forecasts.

Of course, some of this may well reflect the profile of spending this year, for example, with more programmes and projects kicked off earlier in the year rather than later. But overall, it means that borrowing for the first six months is only lower by around £7.5 billion, still some way from the full £20.6 billion forecast for the full 2015-16 year.

It isn’t clear that the OBR is about to make some “helpful” revisions

However, George Osborne’s target is for 2019-20, not this year. What matters is not this year’s tax take and spend, but the OBR’s forecast of how the finances will evolve over the coming years. Analysis by the Financial Times shows that interest payments have fallen, potentially giving the Chancellor an extra £2 billion a year to play with.

But on the other side, economic growth revisions could easily pull in the opposite direction. It hasn’t been very long since the last forecast, but one of the key determinants of whether the Chancellor remains on track will be the OBR’s assessment of economic growth, and how far the economy has to go before it is back at trend levels of growth.

Independent forecasters are now more conservative about the UK’s potential growth in the years ahead than they were back in the summer. More specifically, average forecasters’ estimate of the “output gap”, which measures how much the economy can grow before starting to over-heat has narrowed to around 0.3% in 2015 and 0.1% in 2016. If these forecasts are right, George Osborne could have £2billion to £5billion less to play with than expected by 2019-20.

Overall then, the prospects for helpful revisions are looking mixed.

A few billion here or there isn’t as helpful as it looks

In any case, all of this is arguably a whole lot of spurious accuracy. A few billion here or there pales into insignificance compared to the likelihood of actual revenues and spending numbers in 2019-20 coming out as currently forecast.

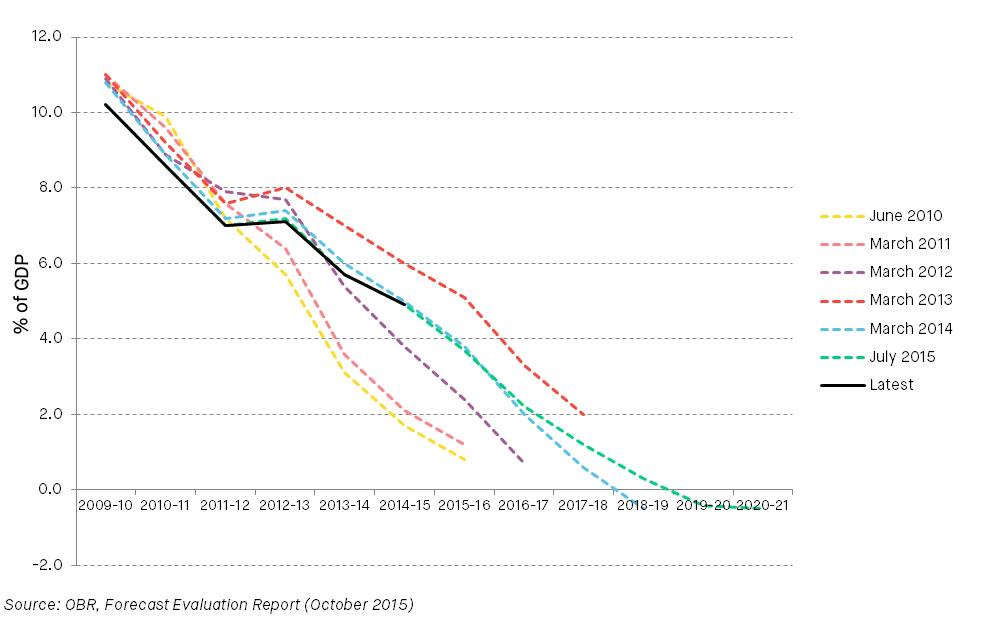

The chart below, from the OBR’s Forecast Evaluation Report shows just how far out forecasts can be. The June 2010 forecast under-predicted the deficit in 2014-15 by £60 billion. That makes even the £10 billion that the Chancellor currently has forecast to spare in 2019-20 look rather small in comparison.

Chart 1: OBR restated forecasts and outturns for public sector net borrowing

In other words, even if revisions do make the numbers look a bit better in two weeks’ time, or even if the Chancellor decides to use up some of his planned surplus to cancel cuts, he could quite easily end up having to pencil those cuts back in again as forecasts are revised in future years.

In truth, only a decision to move away from the ambitious 2019-20 target to run an overall surplus would make the job much easier.

So what could Osborne do?

The Chancellor has set himself a difficult target. He has not made it any easier for himself by making commitments to protect some of the largest areas of spending – healthcare and pensions, as well as education, international aid and defence.

So what are the ways out? There are three options:

- Selling off assets: Plans to sell off assets such as bank shares and parts of the student loan book have become a common occurrence in recent years. Earlier this year, it was reported that Government was considering selling Channel 4. However, if the Chancellor wants to hit his target, timing will be important: it’s the deficit in 2019-20 that counts.

- Changing the boundaries: Whilst some areas of spending enjoy protected status, it is highly likely that those budgets will be increasingly called upon to ease pressures elsewhere. That can happen without deliberate action, for example, cuts in social care tend to result in higher NHS costs due to more admissions to hospital. Or it can be deliberate, for example, by creating ring-fenced funds within the NHS budget designed to support greater integration between health and social care.Other protected budgets are also being used to fund purposes that ostensibly lie outside their remit. A recent example is the Chancellor’s plan to use part of the international aid budget to help councils fund costs associated with new migrants. Other options include putting more of the committed defence budget towards R&D to help counteract potential cuts in R&D spending in other departments such as BIS.

- Finding other people to pay: Finally, we have already seen Government creating new ways to pay for services. The apprenticeship levy, designed to fund apprenticeships from money raised directly from businesses, is one example. Other ways of shifting costs away from taxpayers include switching from grants to loans and placing obligations on organisations and private companies to deliver specific services.

Achieving the deficit reduction target is unlikely to look much easier this Autumn than it was back in the Summer. Expect some creative measures to keep public services ticking over in the Autumn Statement.