If you recently received our SMF Monthly newsletter and are looking for a blog on curriculum reform in England, Scotland and Wales, click here.

The Taskforce for Innovation, Growth and Regulatory Reform published its final report recently. The Taskforce – spearheaded by three veteran Conservative MPs – was set-up to examine how the UK’s regulatory environment, after Brexit, could be improved in order to foster more innovation and facilitate the competitiveness of high-growth sectors of the economy. The report was far from perfect, but more balanced than many might have feared. This blog looks at some of the good bits and the bad bits.

Moving on from the sterile debate of the past

The debate over regulation has been cast in simplistic, binary terms for too long. There have been, broadly, two camps:

- Those who consider almost any attempt to change the regulatory environment as tantamount to returning to putting “children up chimneys”.

- Those who believe that de-regulation is a silver bullet solution, which should be repeatedly fired at the UK’s long-term economic problems.

The debate, no doubt, has been so bifurcated at times because of its ultimate unimportance: until recently, Britain’s regulatory environment has largely been shaped by the EU.

Now, the contours of the old debate need to be urgently cast aside and new ones, more conducive to better policy-making, need to be developed.

A realistic debate requires the recognition of some inescapable realities about regulation. The report, in this regard offers hope, as it is not a pean to de-regulation but is much more measured. It appears to accept much of the following:

- The reality of living in an advanced industrial society is that people expect a high level of protection from unsafe products and working environments, pollution and negligent actions or unscrupulous business practices. The public expect laws to be in-place to significantly ameliorate such risks, because many do not believe the market alone will do so. More recent YouGov data (see Figure 1) suggests only a small proportion of the population “agree” that UK businesses currently suffer from “too much” regulation.

- Complex rules are the norm: we live in a complex society and economy, and therefore there is a minimum degree of complexity which no regulatory framework can plausibly fall below.

- There will also always be a need to adapt to changing circumstances, unless society is willing to accept that products, technologies and behaviour be subject to rules that are outdated and therefore ineffective.

- The benefits of some regulation (e.g. many commercial and corporate laws) are so significant, to both business and wider society, the need for such laws (in principle) is axiomatic. Although, the specific content and design of such rules should always be up for debate.

- Some rules are helpful in protecting lives and well-being to such an extent, that almost any economic costs are worth paying. Although it should be noted that such rules do, often, generate some incidental economic benefits too.

- Analysis of the impact of regulations on SMEs at the firm level, for example, suggest there is rarely a clear and unambiguous pattern of impacts from regulation. Context is a key determinant of whether a specific regulation or the regulatory environment more generally is a “net cost” or a “net benefit” to an individual enterprise. However, the preponderance of evidence on the impact of regulation on sectors, across business size categories and at the macroeconomic level, does appear to be clearer. Poor-quality regulation and indeed “large volumes” of regulation can have detrimental impacts on the prosperity of an economy.

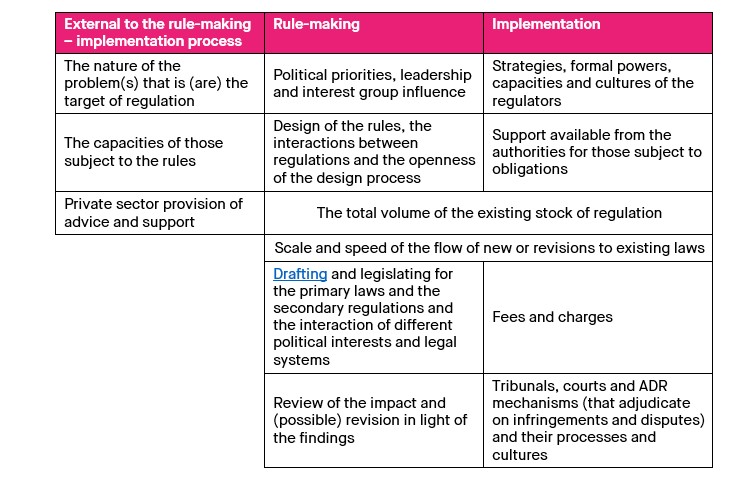

- The costs of regulation to the business community, for example, do not solely stem from having “too many” rules, an assumption that seems to underpin much of the “binary” debate of the past few decades on the subject. Even seemingly simple metrics such as the volume of regulations is more nuanced because it is a function of a number of factors, which include design, drafting and lobbying. Rather the costs come from the complex interaction of a range of factors relevant to regulation and regulatory policy-making, many of which are set out in Table 1 below.

- A society – through its decision-making structures – needs to decide what trade-offs it is happy to make, which requires transparency in policy-making, including the deployment of good data, and clarity from politicians at elections about their regulatory intentions. Too much regulation, because of its technical and often specialist nature –is generated “under the radar”, even though some of it can have far reaching implications for many in society.

- In the end, the variety of factors which influence the impact of regulation on society and the economy is extensive and they interact in complex ways. Therefore, policy discussion about regulation policy should reflect this and regulation should be thought of and understood as a “system” and not just an agglomeration of separate rules and institutions which implement those rules.

Table 1: the “system” of factors that determine the impact of regulation on society and the economy

What, in the report, is good

The overall tenor of the Taskforce report will contribute to moving the regulation debate in this country onto a more reasonable footing. If for no other reason, it should be welcomed. However, there are other reasons to appreciate it, too. These include a number of the positive observations and suggestions that are made in it, including:

- The emphasis on improving the regulatory policy-making process in Whitehall, for example, is welcome. Albeit the specific measures in the report are likely to fall short of being sufficient to generate the transformation in how central government thinks about regulation, that is needed.

- Proposing embedding the objective of “facilitating” innovation, in the UK’s approach to regulation. While this may not be possible in all cases, minimising negative impacts on innovation is a worthwhile goal and should be something those proposing new rules have to seriously consider and justify their proposals against.

- Arguing for a number of reasonable specific reforms to existing regulations, such as getting rid of GDPR – which has to be a serious contender for the worst law of the last decade – and replacing it with a bespoke legal framework, that is more up-to-date and proportionate.

- The stress it places on the benefits of moving from a “hazard”-focussed approach to much regulation (which is predominant in much EU law-making and is intertwined with use of the “precautionary principle”) and shifting the UK’s regulatory framework more strongly towards being (primarily) a risk-based one, with a new “proportionality principle” playing a central role in that.

- Signalling the possible gains that could accrue from re-fashioning existing rules inherited from the UK’s tie as an EU member to ones more aligned with our common law legal traditions, as well as being able to design (and implement) future regulations by utilising the many advantages that the common law approach

Where it goes wrong

Despite the positives, there are a number of substantial problems with the report proposals. Four are briefly sketched out below:

- Its suggestion for a lead Cabinet Minister and a Cabinet Committee for ensuring the regulatory reform agenda is implemented falls short of the scale of the institutional reform that is needed in government to “get to grips” with bringing change to the “Regulatory State”, including its structures, processes and outputs. Driving things from the centre has proven difficult in the British system for a long time. A serious regulatory reform agenda that genuinely aims to succeed needs not only determined leadership from the top, but to be embedded in each department at all policy-making levels and across all parts of the UK, with the senior leaders in Ministries, for example, having “skin in the game” to ensure it is prioritised.

- The report proposes returning to the “one-in, two-out” rule for new regulatory proposals. This is a regulatory “quid pro quo” policy, Which was described by BEIS in the following way, when it was introduced in 2013:

“…every new regulation that imposes a new financial burden on firms must be offset by reductions in red tape that will save double those costs”.

EU laws have been exempt from this requirement, for the obvious reason that they were largely out of the ambit of control of the UK government. However, Brexit has rectified this ”gaping hole” in the previous implementation of the policy. Nevertheless, other problems with the system remain. Perhaps the most serious being the frequent failings of Regulatory Impact Assessments (RIA) to accurately measure the costs and benefits of a regulatory proposal. Errors on the “cost side” for example, include examples of significant underestimations of the administrative and compliance costs of proposed laws and the failure to take account of the potential long-term dynamic impacts of regulatory proposals on competition and innovation, among others.

- A third difficulty is the professed preference for outcomes-based design of regulations. A default preference for such an approach to rules is likely to lead to some poor law making. Outcomes-based rule-making can have a role in any regulatory framework, but its usefulness tends to be context specific. There are downsides as well as upsides. Therefore, making it a key organising principle for the future regulatory environment comes with risks. Laws that mandate outcomes can mean too much vagueness in the rules, creating uncertainty and compliance risk for entrepreneurs and businesses and, consequently, generate significant extra costs for businesses, in addition to the usual administrative and compliance costs that come with any regulations. There is also a risk, that outcomes-focussed rules end-up being too prescriptive because of efforts to avoid the uncertainty associated with vagueness described above. This would ultimately undermine the point of the outcomes-based approach.

- The report doesn’t appear to examine some of the more successful examples from abroad, about how to implement regulatory reform. While not that well known, one of the more best examples of how to succeed in long-term reform comes from British Columbia (BC), where an extensive regulatory reform programme has been associated with improved comparative economic performance since the early 2000’s. Begun by a Liberal BC government in 2001, its achievements and the reform momentum it created have largely sustained over the two decades since it began. Not least because of the way it embedded its reforms across department and agencies in BC. The programme had a number of elements, including updating existing laws to ensure they remained “relevant and effective”, taking steps to make it easier for people and businesses to interact with the BC government, its regulators and agencies and explicitly reducing the number of specific regulatory obligations on BC residents and businesses – which, by 2019, had fallen by 49%. A policy based around the latter obviates the significant problems of trying to estimate the costs of specific regulatory measures and using those estimates as the basis for action. Success relied upon buy-in by leadership both at the highest level and down through all departments and agencies, the right focus for policy (e.g. regulatory requirements not estimates of costs), clear and strict policy rules which create the right incentives throughout government and among regulators, extensive efforts to accurately catalogue all the regulatory burdens on citizens and business, all underpinned by transparency about the process and progress.

What next?

The next few years provide a once-in-a-generation opportunity for putting the UK’s regulatory policy making on a long-term footing, which will serve the county well for decades to come. The Taskforce’s report is a welcome contribution to starting the process of making the regulatory environment “fit for purpose”. Therefore, the current Government is right to welcome the report’s findings and some of its proposals would almost certainly help improve the UK’s current regulatory environment.

However, no report is ever going to be able to adequately consider every aspect of the extensive transformation that regulation-making and the regulatory environment in this country needs. Including what the key lessons are from successful examples of regulatory reform in other countries.

As the Government considers which, if any, of the proposals in the report it might implement, it should, first, look at what the UK could reasonably import from successful places like British Columbia, which have the advantage of offering that rare thing: a tried and tested model of regulatory reform, which the UK could, and indeed should, borrow from.