Access to university is an important political issue, but this is only the beginning of the story.

University is a place where young people grow, develop independent thoughts, learn, establish strong connections and graduate. However, around 8% of young students starting university in London do not make it into their second year, this is the highest of any region in England. The average figure hides the large-scale variation between universities in London, as is shown by the figure below. There are several universities where more than one in ten students drop out of university.

Figure 1: Spread of non-continuation within London 2016/17 (young, first degree UK domiciled students)

Our research, commissioned by the GLA, published this month “Building on success – increasing Higher Education retention in London” builds on our previous research and seeks to understand the factors that could be driving the higher than average non-continuation rate within the capital. The factors are broken down into three groups: student characteristics, university experience and location or regional factors.

We know that those from London are the most likely to attend university and London does exceptionally well at sending the most disadvantaged students to university. Therefore, it is unsurprising that Londoners (those from London before entering university) account for more than half (56%) of the student population within London. Our research uncovered that Londoners are also the most likely to drop-out of university within London, with more than one in ten Londoners not continuing their studies.

London’s student population is diverse, less than half of students in London are White, compared to almost 70% in England. There is a clear difference in retention by ethnicity, as 13% of Black students in London do not continue their studies compared to 8% of White students. Black students are more than 50% likely to withdraw from their studies. Our research suggests some of these differences in the drop-out rates between ethnic groups can be explained by a range of factors including accommodation, prior attainment and socio-economic status.

More than four in ten students in London live in their parental or guardian home – this increases to six in ten for Black students (although lower than for Asian students). Living at home can reduce a student’s ability to make connections and can come with long commutes. This group of students represents a large proportion of the student population in London and universities must do more to adapt their ways to meet the needs of this population.

Prior qualifications also matter. BTECs are a vital route into university for students from lower socio-economic backgrounds (see here). However, such students are also much more likely to drop out: 16% of students who enter university via an access course and 15% of those who enter with a BTEC do not finish their studies.

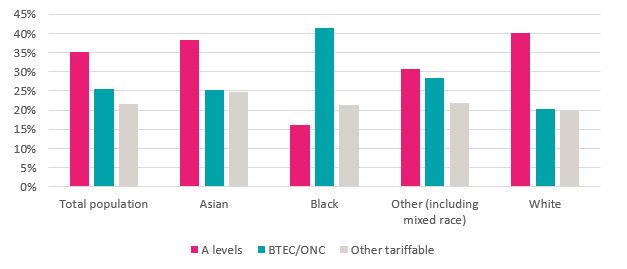

There is a vast difference in the qualifications held on entry to university in London by ethnicity.

Figure 2: Top three qualifications held on entry to university in London by ethnicity

Black students are twice as likely to enter university with a BTEC compared to White students. Young people interviewed as part of this research who had entered university with a BTEC reported a lack of support and difficulties adapting to university study. Very little attention is paid to the needs of students entering university without A levels. Newspapers are full of headlines on A level day, but we do not celebrate the successes of those studying BTECs to the same extent. More needs to be done to encourage and support those entering with BTECs which is becoming an increasingly common route into university. Tools to help support these students could include better curriculum matching between BTECs and degrees, summer school university preparation and targeting of university academic support.

Whilst this research has focused on full-time young students, very little is known about the factors affecting the non-continuation of part-time or mature students who have a considerably higher non-continuation rate than young students. In England, mature students are more than twice as likely as their young fellow students to not continue with their studies, with more than 12% not continuing. If a person has been ambitious enough to enter university beyond the traditional age bracket, for them to not be continuing with their studies represents a significant loss to society and the economy. Very little political attention is paid to this group and more must be done to understand their needs.