The idea of the “Northern Powerhouse” has potential – but in practice has drifted away from the economic theory it is based on, and faces key challenges of finance and regional skills disparities.

In the latest of our ESRC-sponsored Ask the Expert seminars, Dr. Neil Lee – Assistant Professor in Economic Geography at the London School of Economics – discussed the economics of the “Northern Powerhouse”.

George Osborne describes the “Northern Powerhouse” as “a vision based on the solid economic theory that while the individual cities and towns of the north are strong, if we enable them to pool their strengths, they could be stronger than the sum of their parts”. This vision has been put forward as a solution to the UK’s regional disparities. David Cameron argued that joining together cities in the North could “close the north-south gap” entirely.

But are Cameron and Osborne likely to succeed, and has the economic evidence really guided or driven policy on the Northern Powerhouse? To answer these questions we need to understand some basics of ‘agglomeration economies’ – the benefits that come when firms and people locate near one another in cities and industrial clusters.

Cities can give three key types of benefit: sharing, matching, and learning. Sharing occurs when, for instance, high population density allows for a more efficient way of sharing infrastructure. Matching can occur when particular specialisms are in the same place – a specialist research department at a university, together with a cluster of technology firms making use of the skills arising from it, for example. Cities also allow people to see what others are up to, allowing learning to take place.

Productivity tends to be higher in cities, particularly for knowledge based industries such as financial services. London, for instance, has productivity around 35% higher than elsewhere in the UK.

However, much of the policy on the Northern Powerhouse has tended to drift away from justification based on economic theory. Osborne has argued in particular that several ‘ingredients’ are needed to build a Northern Powerhouse – but each policy prescription strays somewhat from what economic theory would suggest as most beneficial.

One ‘ingredient’ is transport. Osborne has advocated rail and roadbuilding projects in the North. But economic theory would suggest a focus on reducing congestion where it is most problematic, and where the benefits would be most pronounced – in short, roadbuilding in London and the South East, where both congestion and economic activity are highest.

Another ingredient is devolution. Policymakers are convinced of the benefits of devolution; but the academic evidence base on devolution is very mixed. Devolution is likely to happen for political reasons, but the evidence on whether it will help drive local economies is very inconclusive. Key questions include exactly what is devolved, and also how much it would cost.

In general terms, the economics and policy of the Northern Powerhouse are not well aligned. There are three particular problems. First, there is an economic rationale to focus on one place, but a political rationale to ‘spread the jam’. The most immediate economic benefits tend to stem from concentrating public investment, but politically it can be easier to spread public funds more widely. Nevertheless, there is some evidence that long-term benefits could arise from investment even when it is not well focused. And the Northern Powerhouse has been effective as a political tool to allow the Government to take bets on local infrastructure investment.

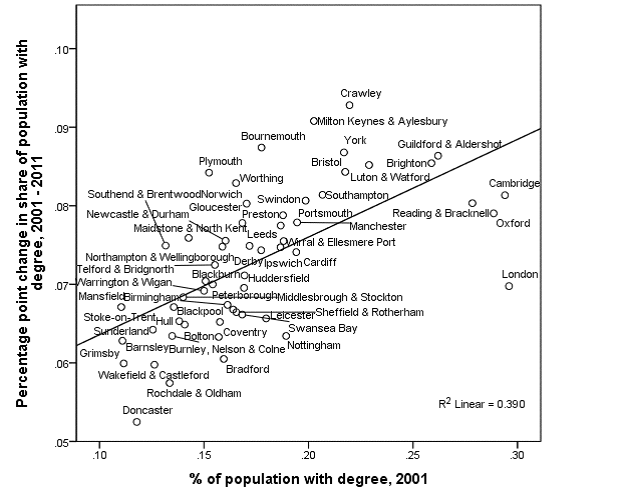

Second, the focus on the Northern Powerhouse misses the key determinant of regional disparities: levels of skills and education. People in the South – and particularly places like Cambridge, Oxford and London – tend to be better qualified. Moreover, people with qualifications tend to move to places where other people are also well qualified, concentrating skills in particular areas (see chart). Skills and qualifications are very important: when demographic characteristics are controlled for, London’s ‘productivity premium’ reduces from around 35% to just 7%, suggesting that much of its productivity advantage can be explained by the characteristics of its residents, rather than its size.

The third problem faced by the Northern Powerhouse is accounting. There has been some new money, but not much. Once funds that were already committed are excluded, a best – very rough – estimate is around £10bn. But this should be put in the context of significant local government cuts in the North; and can be compared to the £14bn cost of Crossrail. It’s hard to see regional disparities being addressed in this context.

The Northern Powerhouse is a nice idea. It builds, in part, on agglomeration theory, together with the idea that larger cities are more productive. However, policy has drifted considerably from the initial idea of joining cities in the North. Big challenges remain. It is hindered by limited finance, which is exacerbated by cuts elsewhere. It also misses the main determinant of regional disparities – differences in levels of skills and education.