Fraud is now the most common crime in England and Wales, costing the UK economy £137bn each year. In this blog, Richard Hyde, Scott Corfe and Bill Anderson-Samways examine the inadequacy of police resource dedicated to tackling the problem, and call on the Government to take a comprehensive “systems approach” to tackling fraud, enacting reforms that can endure over decades.

Fraud is now the most common crime in England and Wales. It costs the UK £137bn a year and generates countless amounts of misery for its victims. What’s more, it’s growing rapidly, largely due to our increased collective presence online – which is where the majority of fraud takes place.

Further, despite common stereotypes, fraud affects all age groups (and indeed, most demographics) fairly evenly. Younger people are actually slightly more likely to be victims of fraud than older people.

Inadequate policing effort against fraud

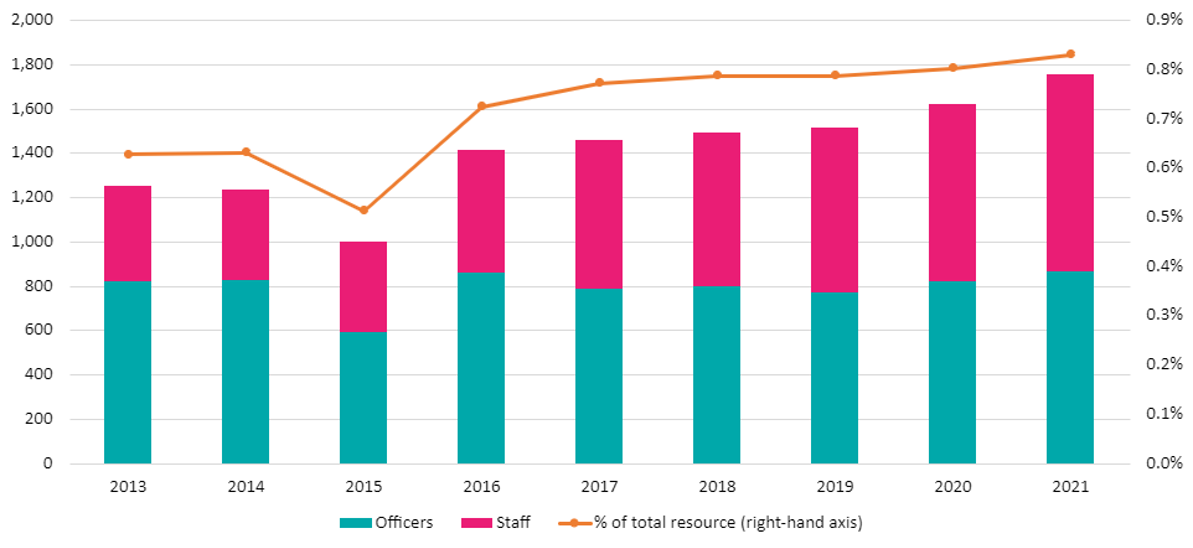

Despite the growth of fraud, and its cost to society, very limited police resource is dedicated to tackling the problem. According to official statistics on the police workforce in England and Wales, just 1,753 officers and staff in 2021 were primarily focused on economic crimes such as fraud – amounting to just 0.8% of the total police workforce. This proportion has seen very little movement in recent years, despite the surge in such crime that has taken place.

Figure 1: Police officers and staff focused primarily on fraud, full-time equivalents

Source: SMF analysis of Home Office statistics

We estimate that there are just 2.1 police officers and staff primarily focused on economic crime, for every 1,000 recorded fraud instances in England and Wales. If one takes into account fraud not recorded by the police, using figures reported by households in the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW), this figure stands at an even lower 0.4 officers per act of fraud. Put another way, for each police worker dedicated to fraud there are 2,500 crimes per year.

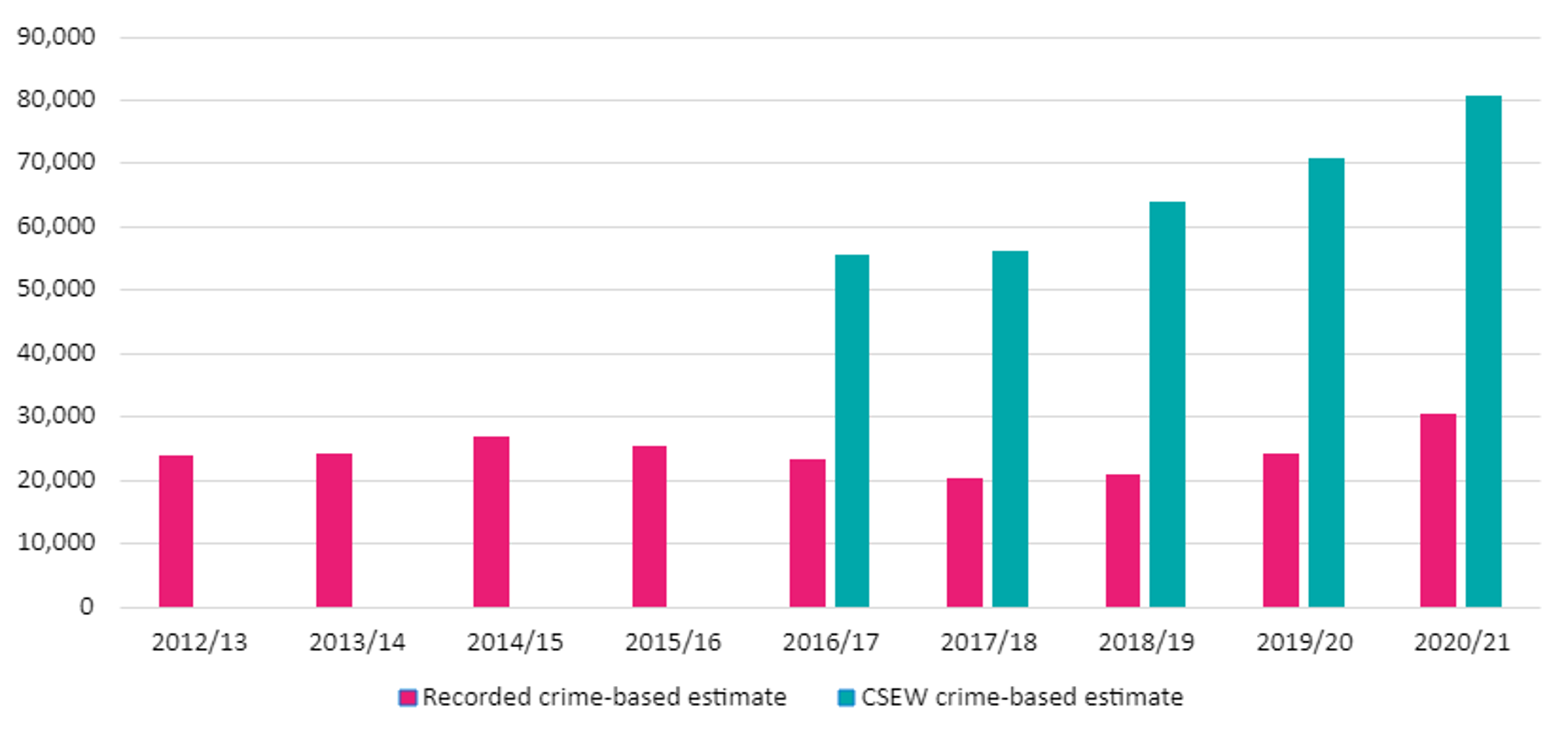

According to police-recorded crime statistics, fraud accounted for 15% of all crime in 2021/21, a figure that rises to a shocking 39% in the CSEW (up from 13% and 30% respectively in 2016/17). We believe this means that a rapid and substantial increase in public resource devoted to fraud prevention and prosecution is required, with the share of officers and staff primarily focused on the issue becoming more proportional to its share of crime, rather than the paltry 0.8% seen at present. On the police-recorded crime data, this would imply an expansion of police resource of about 30,000 additional full-time equivalent staff primarily focused on fraud. If the higher rates of crime suggested by the CSEW are to be believed, this figure would rise to about 80,000. For context, on 31 March 2021, there were 135,301 police officers and 75,858 other police staff in England and Wales.

Figure 2: Extra police resource primarily focused on fraud needed to be proportional to fraud’s share of total crime

Source: SMF analysis of Home Office statistics and Crime Survey for England & Wales

An opaque and complex law enforcement landscape

But resolving this issue must not just be about expanding headcount – the UK’s existing institutional landscape for dealing with fraud is a mess. The City of London Police (CLP), the national lead force on fraud, depends on annually-decided Home Office grants for its fraud-tackling activities. This disincentivises long-term planning and investment. Below the CLP are Action Fraud (a service operated by the police where fraud cases can be reported – but rarely are), and the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (NFIB – which analyses reported fraud cases, prior to investigation). Neither of these organisations can keep up with the rapidly-increasing volume of fraud cases. They lack sufficient staff. Their technical systems are outdated. They are underfunded.

The fraud cases which make it through this tight gap – still an enormous number – are then sent to local police forces for investigation. This in itself creates problems, because the organisations which best understand fraud (the CLP and its organs) are not the ones that actually deal with fraud cases. Local forces therefore often find themselves ‘muddling through’. Sometimes they don’t even realise that they are responsible for dealing with the fraud referrals, viewing the issue as being ‘owned’ by the NFIB. And of course, local forces suffer from their own funding pressures. It is therefore no surprise that they often treat fraud as a low priority.

To top it all off, although the CLP is responsible for improving this situation, none of the local forces are actually accountable to the CLP. And the National Crime Agency (NCA), which deals with organised criminals – the main perpetrators of fraud – does not work directly on fraud. Overall, the result is an opaque, complex, and uncoordinated landscape where resources are scarce and there are insufficient incentives for the police to take fraud seriously, to a degree commensurate with the scale of the societal cost that it generates.

A step-change in efforts to deal with economic crime

Tackling fraud effectively would deliver a substantial reduction in fraud levels and boost the economy and wider wellbeing of society. One estimate suggested that reducing it by 40% would save the country £55bn a year.

Getting started on reform

No government is afforded the luxury of being able to start afresh in any policy area. This is especially the case with crime and policing, where there is a long history of hyperactive policy intervention and ups and downs in resourcing and an existing organisational framework and Economic Crime Plan and a Serious and Organised Crime (SOC) Strategy currently in place.

Further, it would be unfair to say that there haven’t been some improvements in recent years in some of the structures of policing, that provide some tentative foundations on which to build a better response. These include: the National Policing Board (NPB), the NCA, the National Economic Crime Centre (including the Online Fraud Steering Group – OFSG), the Regional Organised Crime Units (ROCU) and the UK’s successful model for counter-terrorism policing are all precedents that can be built upon in relation to fraud specifically, and economic crime more broadly.

What a “systems approach” should look like

Any government that wanted to put in place a comprehensive “systems approach” to fraud that endured over decades would have to implement reforms on a range of fronts, each of which complements the others:

- Reform needs to begin with focusing on the right outcomes, based on an accurate mapping and understanding of the crime landscape. A key aspect of economic crime is its links (in most cases) to Serious Organised Crime (SOC) groups as the perpetrators of such crimes and the use of digital technologies to commit the crimes. Therefore, economic crime is – for practical purposes – rarely a discrete category of crime but one inextricably entangled with other types of criminality, which should be reflected in the new approach.

- The second step should be establishing the right leadership and oversight structures for a new “systems model” for tackling economic (and associated) crimes, which ensures these categories of criminality are long-term priorities at the national level, and that the performance of law enforcement is accountable for its performance against clear benchmarks. A new leadership group should be established, jointly chaired by the Chancellor, the Home Secretary and Secretary of State for Justice. It should set the overall objectives, oversee the various organisations involved in dealing with economic, cyber and SOC and hold the leaders of law enforcement agencies to account for their performance.

- Third, there needs to be a redistribution of responsibilities across the law enforcement landscape for economic, SOC and cyber-crime. Local constabularies should lose responsibility for economic crime, cyber-crime, and all but the most local instances of SOC. An expanded NCA should take responsibility for inter-regional, national, and international law enforcement efforts across all three areas absorbing the economic crime functions of the City of London Police (including the NFIB), Serious Fraud Office, etc. Alongside, the network of ROCUs should be “beefed up”, put on a permanent footing and jointly run by the NCA and the relevant local constabularies, and should deal with intra-regional economic, cyber-crime and SOC.

- The fourth strand of reform that is needed is the sustained improvement in the capacity and capability of the NCA and the ROCUs and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) to tackle economic crime (and associated crime-types: SOC and cyber-crime) along with improved management and incentives to encourage higher performance. The recruitment of more than 30,000 new police and expert civilian staff will be required if manpower resources are to reach levels more commensurate with the scale of economic crime. The CPS will similarly need to see expansion. Pay and other terms and conditions will undoubtedly need to be reformed to compete with the private sector for talent, as well as the provision of sufficient high quality training for officers, civilian staff, and prosecutors in skills such as forensic accounting and digital forensics, etc. Boosting capability and capacity on the scale needed will require a fully costed manpower strategy for policing and the CPS for the next decade, that all political parties are happy to commit to. In addition, there will need to be operational innovations, with an explicitly pro-active philosophy to pursuing criminals among the agencies with responsibility for dealing with economic, cyber and SOC, which might be expected to include a more aggressive approach to asset recovery and the activities of “key enablers” such as lawyers and accountants as well as more licensed scope for innovation in investigation and prosecution.

- The fifth element that needs attention is the contribution of the private sector. The latter’s involvement (e.g. the financial services industry and tech platforms) is key to successfully preventing fraud in particular, and economic crime, cyber-crime, and SOC more broadly. This is because the private sector operates the infrastructure through which fraud, for example, takes place. The private sector is also the repository of substantial specialist investigative capability that could be leveraged by law enforcement. However, the current partnership between the state and private sector embodied in forums such as OFSG is failing to deliver at the pace and on the scale needed. Therefore, a new legal framework is needed – building on ideas like corporate liability for economic crime – to create the right incentives for stronger action by the private sector to “design-out” fraud and other crimes as much as possible. Further, actions to reduce the facilitative role of some intermediaries is needed. In addition, methods for leveraging private sector expertise more extensively into the pursuit of criminals need to be explored. Formal deputizations of specialists in the private sector, to add pursuit capacity and capability to the public sector, is one option that should be explored by the Government.

- The sixth aspect that the “systems approach” requires some attention be paid to, is the current legal framework around economic crime, cyber-crime and SOC. There is currently a myriad of laws – brought in piecemeal over long time periods – relevant to tackling all three types of crime.[1] Inconsistencies and gaps in the current body of law need to be dealt with and any necessary modernisations implemented. This should include expanding the law enforcement tool box by providing more civil powers that can be used alongside criminal sanctions. A process of regular reviews of the legal framework needs to be instigated to ensure it stays up-to-date and as usable as possible by enforcement authorities.

- Allied to consolidating and updating the criminal law, is the seventh element in the “systems approach”, namely reforming the criminal justice process associated with economic crime. In 2001, the Auld Review proposed removing juries from complex fraud trials. This should be re-visited as an idea. The Government should look to develop specialist courts for economic and cyber-crime and SOC along with enhanced sentences for those facilitating or committing economic crime, in order to strengthen the disincentives against committing such offences as well as increasing the period of incapacitation of perpetrators.

- Considerable amounts of economic crime, and fraud in particular, have an international dimension. More cooperation across borders by enforcement agencies is therefore required. The UK Government should pursue efforts to harmonise key processes that hinder cross-border cooperation, such as forensic-technical standards for exchanging electronic evidence between law enforcement agencies. Such efforts should be part of a wider push by the Government to work with other countries to review and enhance (where necessary) the existing relevant treaty landscape[2] as well as providing direct support to help less developed countries grow their indigenous capabilities and capacity to tackle economic and cyber-crime and SOC.

- The success of the “systems approach” will rely on at least 30,000 additional staff (officers and civilian specialists) being recruited and will therefore require sufficient funding, committed over a long period of time, if the step change in effectiveness against fraud specifically and economic, cyber and SOC more generally is to occur. This will require a more fundamental look at the Police funding formula after the redistribution of policing responsibilities, more scope for local revenue raising for local policing and a willingness from the Treasury to invest substantially more money from the “central pot”, on a sustained basis. Alongside the extra funding for policing, there will need to be a concomitant increase in the monies available to the CPS.

- The final requirement for making a new systems-based approach to tackling fraud is a change in public discourse. A great deal of public and political debate around crime focuses, sometimes exclusively, on more familiar and conventional forms of crime, and on their traditional remedies. A political debate on crime that where talk of “bobbies of the beat” is a major element is unlikely to properly inform the electorate about the nature of crime in the round or create the political conditions required to underpin the significant changes required to better address fraud. Leaders should speak honestly to voters about the changing nature of crime and the new approach that is needed to best address it.

[1] These laws include: Theft Acts 1968 and 1978, the Forgery and Counterfeiting Act 1981, the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, the Malicious Communications Act 1988, the Computer Misuse Act 1990, Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005, the Fraud Act 2006, the Serious Crime Act 2007, the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011, the Serious Crime Act 2015, the Investigatory Powers Act 2016, the Data Protection Act 2018.

[2] Some of the relevant treaties include the network of Mutual Legal Assistance (MLA) treaties countries agree bilaterally, as well as the 2001 Budapest Convention on Cybercrime and the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. In addition, agencies like long-standing Interpol play a vital role in facilitating intelligence sharing, and could also benefit from being strengthened.