The United States is currently facing a devastating opioid crisis, with potent synthetic opioids such as fentanyl driving increasing overdose deaths. While these drugs have not yet taken a firm hold in the UK, the domestic situation could get considerably worse. In this blog, Jake Shepherd discusses the potential impact of the evolving drug landscape, including measures that could be taken to avert crisis.

Fentanyl is a strong opioid. Like other opioids such as morphine or oxycodone, it can be used pharmaceutically and is prescribed to treat severe or long-term pain. Producing a strong high, including feelings of euphoria and relaxation, fentanyl is also used recreationally.

Fentanyl is extremely dangerous, and can be up to 50 times stronger than heroin. Because it is so powerful, the risk of overdose, especially when mixed with other drugs, is high. Even a tiny amount can be fatal.

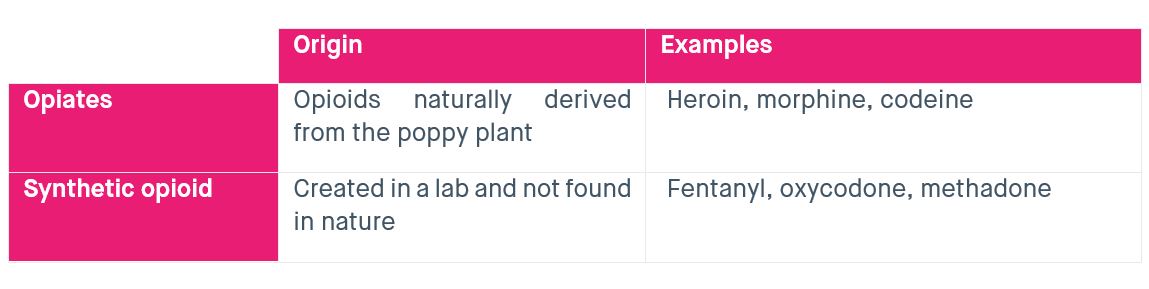

Table 1: Opioid classification

Source: SMF

Fentanyl has not yet established a significant footprint in the UK. However, data from other countries, namely the United States, shows that once such products enter the drugs market they can quickly proliferate – with devastating consequences. Policymakers must stay ahead of the curve and prepare for this potential crisis before, not after, things start to spiral.

America is gripped by a deadly opioid epidemic

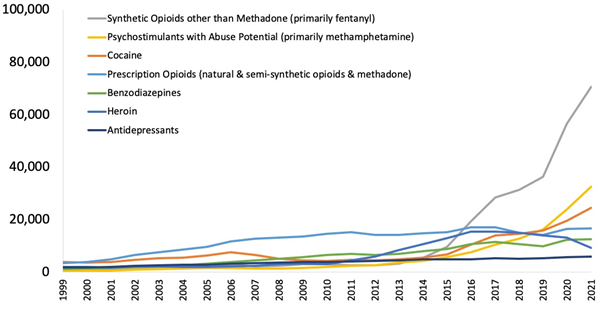

Due to the rapid increase of overdose deaths in recent years, the United States has declared an opioid-related public health emergency. Synthetic opioids have been the main driver of those drug deaths, rising by nearly 23 times from 2013 to 2021 – a year in which nearly 71,000 of the total 107,000 overdose deaths were attributable to synthetic opioids.

Figure 1: Overdose deaths, United States, 1999-2021

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

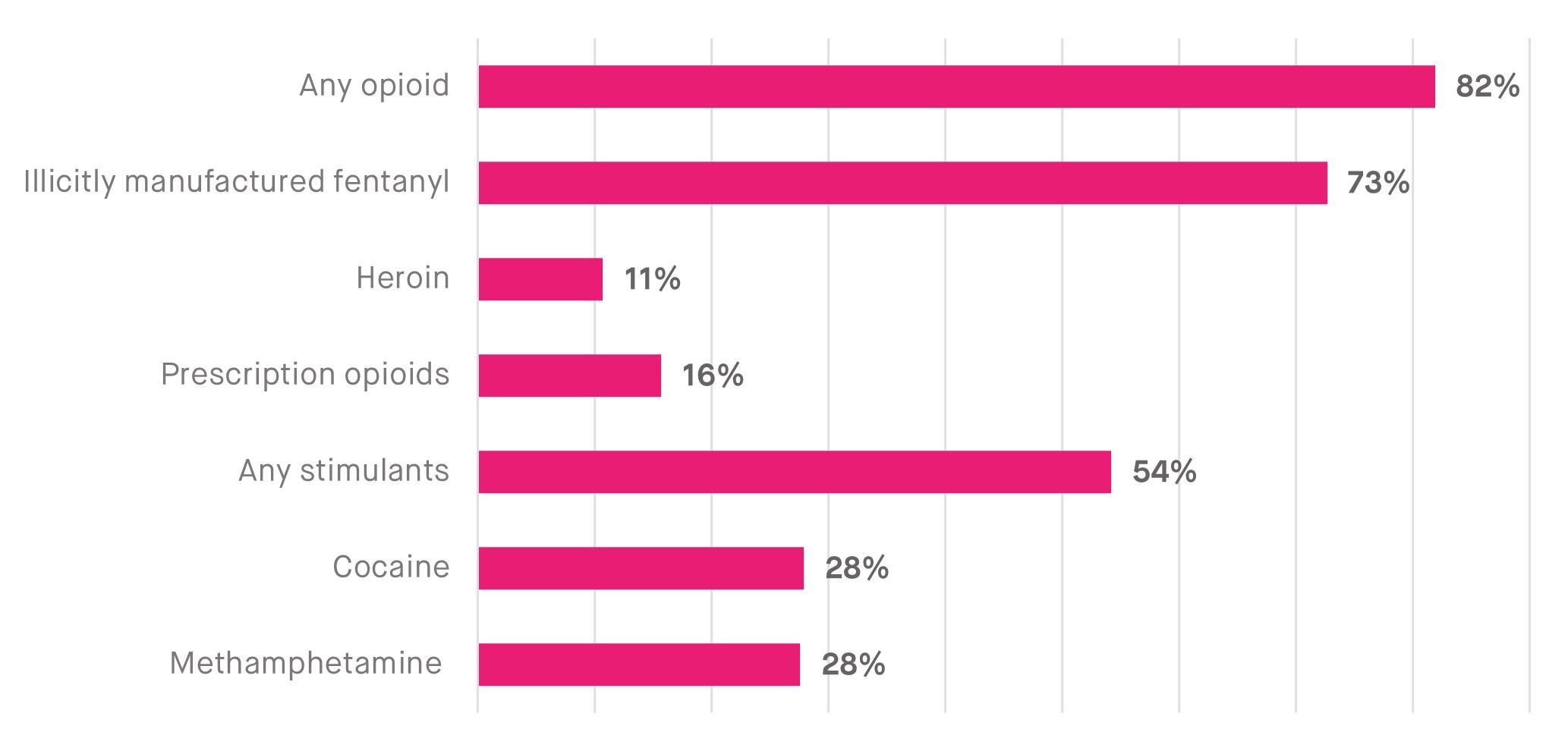

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention attribute this increase in synthetic opioid fatalities to fentanyl in particular. Although some comes from pharmaceutical sources, with prescription fentanyl also carrying a risk of addiction and misuse, most of America’s burgeoning fentanyl supply is identified as being illegally produced. Data shows[1] 73% of fatalities in 2021 involved illicitly manufactured ‘street’ fentanyl, the most commonly involved opioid.

Figure 2: American overdose deaths involving select drugs and drug classes, 2021

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Note: Data is unavailable for some US jurisdictions

The loss of human life due to drugs is tragic, bringing with it a great deal of personal grief. But each overdose also bears social and economic consequences. As highlighted by the Financial Times, the US’ soaring drug death rate, equivalent to an American succumbing to an overdose every five minutes, costs the economy $1.5 trillion every year.

Because of this long trail of suffering and loss, campaigners have called on the White House to declare fentanyl a ‘weapon of mass destruction’. In equally urgent language, Alejandro N. Mayorkas, the Homeland Security Secretary, has labelled fentanyl overdoses “one of the greatest challenges that we are facing as a country”.

Enduring the deadliest drug epidemic in its history, the US stands as a poignant example of a nation deeply impacted by opioids. It is not the only country affected – similar crises have unfolded in Canada and in Estonia – but the scale of the emergency, marked by the loss of many thousands dying annually, sets it apart. To put matters into perspective, in 2021, EU member states collectively reported around 140 deaths associated with fentanyl.

However, with new opioids continually entering the drug market, the potential rise of substances like fentanyl cannot be dismissed. Experts are already questioning if the UK is experiencing its own opioid epidemic. Is it only a matter of time before synthetic opioids start to tighten their hold in British communities?

Synthetic opioids do not have a foothold in the UK… yet

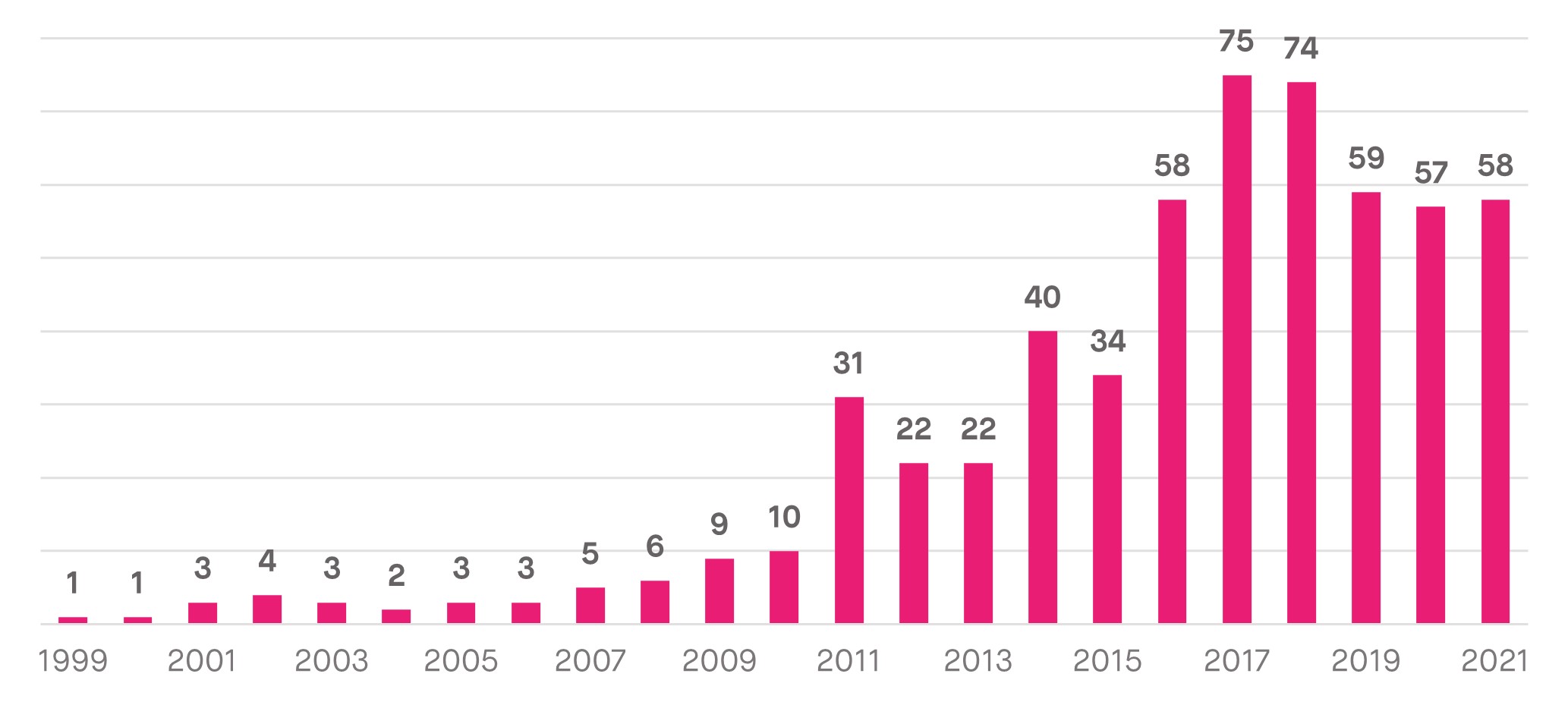

In the UK, the number of reported deaths involving fentanyl are relatively low. According to the Office for National Statistics, there were 58 fentanyl deaths in England and Wales in 2021, accounting for less than 0.1 deaths per 100,000 people. Despite showing a gradual increase over time, these fatalities pale in comparison to the American situation, where the illicitly manufactured fentanyl death rate is 25.0.[2]

Figure 3: Deaths from drug poisoning by fentanyl in England and Wales

Source: Office for National Statistics

While fentanyl is not currently a widespread issue, opioid-related drug deaths are not uncommon. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction estimates the UK has the highest rate of problem drug use for opioids in Europe [3]. In England and Wales in 2021, almost half (45.7%) of all drug poisonings involved an opiate such as heroin and morphine. The most common type of drug implicated in drug misuse deaths in Scotland, the ‘drug death capital of the world’, is opioids, involved in 82% of all overdose deaths.

The ground appears fertile for more potent products entering the market. Indeed, there is already some concern around the increased availability of new, “unusually strong” opioids, some of which contain fentanyl, in circulation in Britain. A specific group of powerful synthetic opioids, nitazenes, have recently been detected in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

At the same time, evolving trade dynamics are poised to facilitate an increased influx of synthetic opiates across UK borders. The Taliban has recently prohibited opium production in Afghanistan, the world’s leading exporter of the substance, accounting for around 80% of the world’s supply. Before the ban, 95% of the heroin found in Britain came from Afghanistan.

If Afghan cultivation decreases, it only seems logical there will be a product vacuum in the UK; a gap in the market for similar substances. Once the heroin supply dries up, dealers may switch to more dangerous products such as fentanyl and nitazenes.

Should they enter the supply chain, displacing existing substances, the American experience suggests synthetic opioids could prove difficult to get rid of. Because they are cheap to produce, dealers may see it as a way to increase their profits by cutting them into other drugs, including those with lower dependence potential, like cocaine. Deadlier than other products, there will be more scope for overdoses. An inflow of synthetic opioids will likely hit the country’s most deprived regions and communities.

Drug market dynamics are complex. It’s entirely possible a fentanyl epidemic doesn’t arrive to British shores. But leaders should be prepared for a surge in the circulation of the drug. Even if the devastation caused by fentanyl doesn’t reach the same scale as in the US, thousands of lives may be at stake.

The UK must take action and address synthetic opioids head-on

Parliamentarians must confront this emerging public health crisis, taking proactive measures to prevent potent synthetic opioids from becoming widespread.

One way of doing that is by overhauling drugs policy, shifting to a liberalised public health framework that prioritises the support and treatment of drug users, rather than criminalising them. This is supported by the Home Affairs Committee, which has recently recommended that current legislation undergoes reform, promoting a greater role for public health in the UK’s response to drugs.

Radical reform could effectively help vulnerable users, as demonstrated by positive decriminalisation outcomes in Portugal. The Portuguese approach has been lauded for its positive impact on drug-related issues, with other countries also taking steps towards decriminalisation. However, liberalisation is a complex process with many potential drawbacks, including the possibility of increased availability and consumption. If implemented poorly, legislative reform could backfire – with disastrous consequences.

Within the current legislative framework, another potential avenue might involve intensifying efforts against the illegal black market, following the example of Estonia’s seemingly triumphant crackdown on fentanyl supply. While this approach could bring short-term success, it reinforces the prohibitionist stance toward users, perpetuating the ever-controversial ‘war on drugs’. Along these lines, the UK government has started banning more synthetic opioids. Other experts endorse a comprehensive public health response, with lessons from tackling other substances showing that prohibition provides minimal assistance to those who are vulnerable.

The government should do more to support evidence-based public health initiatives. In the US, where the need for intervention is all too apparent – and where prohibition clearly isn’t stopping supply – programmes such as syringe services, fentanyl test strip provision, and a drug overdose health alert network have been deployed by authorities in responses to the crisis, as part of opioid overdose prevention strategies.

UK campaigners are concerned about the emergence of a synthetic opioid crisis and are calling upon government to take action before things get worse. A recent report by the social justice charity, Cranstoun, which is supported by relevant partners and undersigned by key health figures, has set out an eight-prong plan for addressing the potential synthetic opioids crisis:

A funding package is required to support the rollout of these proposals. But that would come at a very low cost when compared with the health and economic tolls of a full-blown synthetic opioid crisis. If the American experience tells us anything, it’s that no price is too high for being proactive and intervening early.

In the face of mounting evidence, the need to safeguard the UK from the devastation caused by synthetic opioids is difficult to argue against. With many lives hanging in the balance, the government needs to acknowledge the changing drugs landscape and squarely confront the risk of powerful substances such as fentanyl. It must stay ahead of the curve.

[1] Only the 32 jurisdictions that reported all overdose deaths in their jurisdiction, and had medical examiner/coroner reports for at least 75% of deaths, are included.

[2] Data limited to 32 US jurisdictions.

[3] Data is limited to 24 European countries, covering different years.