This report takes a fresh look at financial capability in Great Britain.

It extends previous work using the Wealth and Assets Survey to understand the nature and drivers of the problem that Britain faces and make recommendations for how capability and outcomes can be improved.

In particular, by using the household nature of the Wealth and Assets Survey and original polling and focus groups commissioned for the report, it assesses how families share responsibilities and asks whether social ties can reduce the impact of individuals’ low financial capability. It highlights three key groups of households where interventions could be targeted and makes suggestions for a way forward.

Britain’s financial capability problem

Financial capability can be summarised as the ability an individual has to collect, collate and assess the information needed to make an informed decision when purchasing a good or service or making choices about their future financial plans.

It is clear that Britain has a problem with financial capability. Previous research has shown that one in three mortgage holders do not know the rate of interest they are currently paying; and half of the UK population have numeracy skills no better than those expected of nine to eleven year olds. Research in this report uses detailed analysis of the Wealth and Assets Survey and methodology previously used by the ONS, Bristol University and FCA to show that:

- Nearly a third of people have low capability in terms of planning ahead financially;

- One in five people score poorly on being able to make ends meet; and

- One in eight people would not be able to last more than a week if they lost their main source of income.

Overall the research suggests that one in every eight people has low financial capability.

The impact of low financial capability

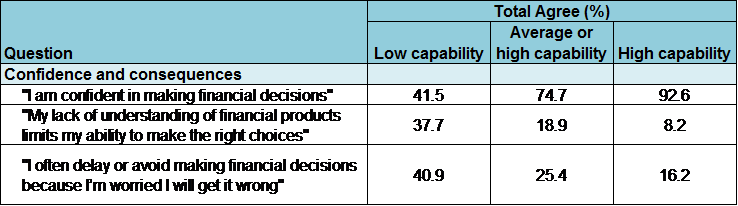

The impacts of poor financial capability can be seen in how individuals feel about the financial choices they make. The table shows that individuals with low capability are significantly more likely to lack the confidence and understanding they believe they need to make the right financial choices. In turn, this leads to them delaying decisions or simply not taking action and limits the extent to which they can actively engage in financial decisions.

Table ES1: Results from polling split by financial capability level

Source: Populus on behalf of SMF

Notes: Base is all respondents with a bank account (1,801)

The impacts can also clearly be seen in individual and family outcomes:

- There are 2.6 million people suffering from severe problem debt and one in six people are in some way over-indebted;

- Consumers are losing out on £4.3 billion a year by keeping savings in accounts with very low rates of interest.

- The average family loses out by around £400 a year if they do not switch energy supplier, current account and mobile tariff. Across Britain this suggests billions of pounds of disposable income lost each year from a lack of engagement.

It is not just individuals and families that suffer. A lack of informed consumer engagement is stifling competition and lowering innovation, productivity and growth across the economy.

Taking a household perspective

Given this evidence, it should be no surprise that there have been a range of attempts from governments, policy makers and wider stakeholders to tackle the issue. However, capability in Britain remains stubbornly low. Urgent policy action is needed to improve capability and outcomes.

A key area for this to focus is on financial capability within households. While the vast majority of previous research in this area has focussed on individual capability, it is clear that individuals do not make decisions in isolation. Often choices need to be made for (or with) other members of a household. For example, choices over a mortgage or utility provider will impact on all household members.

This means that it is the overall level of capability across the household and how household members support each other to make decisions that is important for outcomes. This came out clearly in the focus groups conducted for this report. For example a number of participants talked of sharing household decisions and giving responsibility to household members with greater capability:

“If I need to change something I would probably ask my fiancé to do it…”

Male focus group participant

“…my husband knew that I wasn’t very good with money so he just made the decision that he would do the mortgage and the poll tax so at least we’ve always got a roof over our heads. And then I could do the utility bills and the smaller bills.”

Female focus group participant

This highlights that other household members might play an important role in helping low capability individuals make the right financial decisions. The extent to which this is feasible will be determined by the degree to which individuals with low capability live in households alongside other members with higher capability.

The household nature of the Wealth and Assets Survey allows an analysis of household capability to be undertaken. Table ES2 shows the breakdown of this analysis. Capability poor households are those where all of the members have a relatively low capability. Conversely, capability rich households are those where all members have a relatively high capability. It shows that extreme clustering of low and high capability is relatively uncommon as most households have members with a range of different financial capability levels.

Table ES2: Proportion of households with each financial capability level

| Household type | Proportion of population |

| Capability poor | 1.7% |

| Mixed capability | 95.4% |

| Capability rich | 2.9% |

Source: SMF analysis of the Wealth and Assets Survey 2010-12

These results are used to make recommendations, summarised below, for how engagement, capability and outcomes can be improved for each of these groups.

Capability poor households

While a seemingly small group at just 1.7% of households, this group amounts to at least half a million capability poor households across Britain. Overall, 28.8% of individuals with low financial capability live in these households where decisions over individual or household finances cannot be supported by other household members with an average or above level of financial capability.

These households are almost solely found towards the bottom of the income distribution and the majority are not in work. With many of these families being financially supported by benefits, it is essential (for them and the taxpayer) that this money is used to improve living standards, rather than increase the revenues of firms relying on inertia to drive profits.

To ensure this happens, two new approaches should be adopted or tested to support existing schemes:

- Better deals on benefits: All new claimants of benefits should be offered a free switching consultation. This should work with claimants to understand the range of contracts across utilities and financial service products they are currently under and assess whether better value options could be available. The Government could work with existing aggregator / switching sites to provide this service at relatively low cost.

- Super Switch: The Government should also develop a collective switching initiative. This would be open to all, but particularly targeted at low-income households (for instance by offering to it to new benefit claimants). It would bring together a large number of willing switchers and, in turn, a bulk discounted tariff could be negotiated with a range of providers.

Mixed capability households

Over seven in ten (71.2%) individuals with relatively low capability live with someone with a higher level of capability, suggesting that the role of social networks in mitigating the impacts of low financial capability could be strong.

However, the viability of this approach and the range of potential policy solutions will depend on the attitudes towards supporting, or receiving support from, other household members. Polling commissioned as part of this research shows that those with low capability are less likely to be comfortable talking about their finances than those with average or high capability. However, over half of low capability individuals would turn to family or friends if they were in financial difficulty and more than four in ten low capability individuals would also be comfortable talking about finances with friends and family. For those with average or high capability, the results show a significant majority being comfortable helping friends or family in making choices about their personal finances.

Overall, this suggests that the use of friends and family in making financial decisions could play an important role in mitigating the impact of individuals’ low financial capability: those with higher financial capability are willing to help, and (at least some of) those with lower capability are willing to discuss their finances.

However, there are still barriers. This is particularly true with respect to the extent to which people are willing to talk about their finances. Recent research demonstrates the extreme nature of this aversion to talking about finances in the UK, highlighting that:

After surveying 15,000 men and women, researchers from University College London found that people are seven times more likely to tell a stranger how many sexual partners they’ve had, whether they’ve had an affair, and whether they’ve ever contracted a sexually-transmitted disease than have a chat about their income.

To break down these barriers, focus group participants argued that the subject needed to be made less embarrassing and more interesting. To help this to happen and to get families talking and supporting each other to make better financial decisions, the report recommends the introduction of an Active Consumer Week.

Active Consumer Week: Government and regulators should co-ordinate to rebrand and improve the existing “National Consumer Week”. This should build on the Government’s recent publication, A better deal, and rather than focussing on consumer protection, the new week should look across the whole range of consumer engagement opportunities including switching and protection.

The Government should work with experts in behavioural science to develop a strategy for making the most impact with Active Consumer week. This should look to explore ideas for making it more of a social norm to discuss finances during this week and also communicate the potential benefits of engagement.

The regulator could also have a role in prompting discussions with friends and family members:

Changing risk warnings: To prompt discussions with others with potentially higher capability, financial risk warnings could highlight the benefits of discussing decisions with others. For example, when taking out a loan or short-term credit, this could be a formal part of any product journey with regulated questions being asked as to whether you have spoken to a friend or family member about whether it is the best decision for you. Similar prompts could be provided as part of advertising for financial products and services: for example, stating that ‘…your capital may be at risk; and many people find that it’s useful to chat to someone about a big decision like this.’

Capability rich households

There could also be important policy interventions for households classed as capability rich. More broadly, these approaches will also support mixed capability households.

One in ten people with high capability believe that their lack of understanding limits their ability to make financial choices and one in six with high capability delay or avoid making financial decisions because of a fear of getting the choice wrong. This suggests that prompting greater engagement from this group could increase their living standards and help them make better decisions.

There are also much wider potential effects on the market. For instance, active engagement by this group could help drive competition and innovation across the market. In turn, by supporting this group of capable by cautious households to engage more actively, consumers and households across the whole market could gain. The economy would also gain.

Two recent Social Market Foundation reports, Should Switch Don’t Switch: Overcoming-consumer inertia and Balancing Bricks & Clicks: Understanding how consumers manage their money, outlined recommendations that could be effective in ensuring this happens.

Recommendations included:

- Improving the midata scheme: Implementing a full review of the midata scheme to understand why it has had a relatively low impact. Building on conclusions coming from the review, firmer action is needed to move to the next iteration of the midata scheme.

- Facilitating the open API standard: To ensure this has the impact it should, work is needed to reassure consumers using such services and protect them if something should go wrong.

- Consulting on a Unified Data Portal: Taking the principle behind the API standards and midata scheme to the next level would mean developing a Unified Data Portal. This could allow consumers to choose a third party provider to hold their usage data from a range of sectors. Firms would update it automatically and consumers could access all their data and a set of personalised recommendations all in one place. A consultation is needed to understand how this could be taken forward in practice and how to ensure that consumers (and their data) are appropriately protected.

Boosting financial capability, improving living standards and growth

This report demonstrates the poor level of financial capability across Britain and the impact it has both on individual living standards and wellbeing and, more generally, on the economy and growth.

Tackling this will not be easy. Many schemes have attempted to do so before and have largely failed. The report suggests that to ensure that future schemes are more successful, a household approach needs to be taken. This would consider the links between household members and the fact that individuals do not make decisions in isolation. The support that household members can give each other will be essential in improving outcomes.

By targeting support on the 500,000 households with the very lowest capability; encouraging financial discussions between household members and wider social networks; and super-charging the engagement activity of those with already high capability, a significant improvement in financial capability, consumer engagement and outcomes could be delivered across Britain.